I came home from Oaxaca ahead of schedule, something I’ve never done before. After 15 days, I was exhausted. Each day the heat and the humidity sapped me. At night, I’d recover, but not 100 percent, so I started each subsequent day with less than a full recharge. I walked five to eight miles a day. I had a thirst I could not slake, even with a several bottles of water at a time. I lost nearly five pounds. My rented room held the heat and sleep never really arrived for long. The day before I decided to leave, I played basketball with a group of kids for 90 minutes. Afterward, my body barked in loud protest. I answered by changing my flight.

I came home from Oaxaca ahead of schedule, something I’ve never done before. After 15 days, I was exhausted. Each day the heat and the humidity sapped me. At night, I’d recover, but not 100 percent, so I started each subsequent day with less than a full recharge. I walked five to eight miles a day. I had a thirst I could not slake, even with a several bottles of water at a time. I lost nearly five pounds. My rented room held the heat and sleep never really arrived for long. The day before I decided to leave, I played basketball with a group of kids for 90 minutes. Afterward, my body barked in loud protest. I answered by changing my flight.

Part of me feels like I gave in, like I allowed a bit of discomfort to drive my decision. That’s my 30-year-old ego talking. Another part of me is soothed by the cool ocean air and the opportunity to stand in the scalding stream of the shower for as long as I want. That is the sound of seven biological decades exhaling in relief.

I returned with a few strong photographs and with memories whose images are even more powerful. Together, they illustrate the great challenge of photography, the effort to preserve with the camera what is seen by the mind’s eye and felt by the soul. I am proud of my photographs, but I am also frustrated by my inability to gather into a frame the vividness, in all its glory and in all its pain, of life in Oaxaca.

When I stand on a Oaxacan street corner and see and hear and smell the chaos around me, I want the camera to vacuum it all in – the noise of the buses, the smell of the sewage and the food vendors, the hunched shoulders of the working men, the wide-bodied grandmothers making passage on the sidewalks with their hips, the sweat and the sun and the steam of the humidity. I want all that in a photograph. That is the picture I have yet to make.

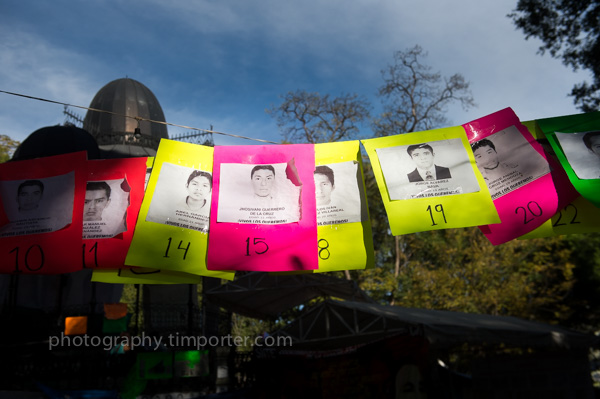

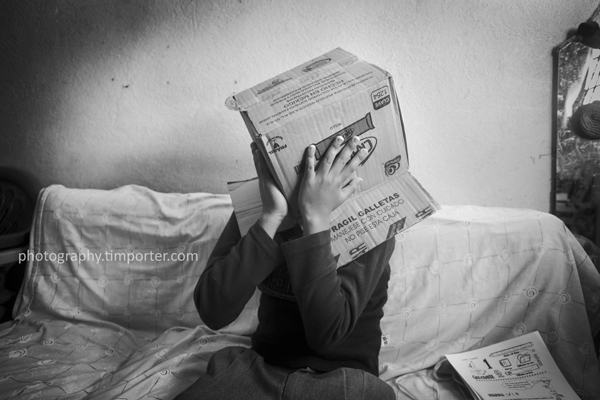

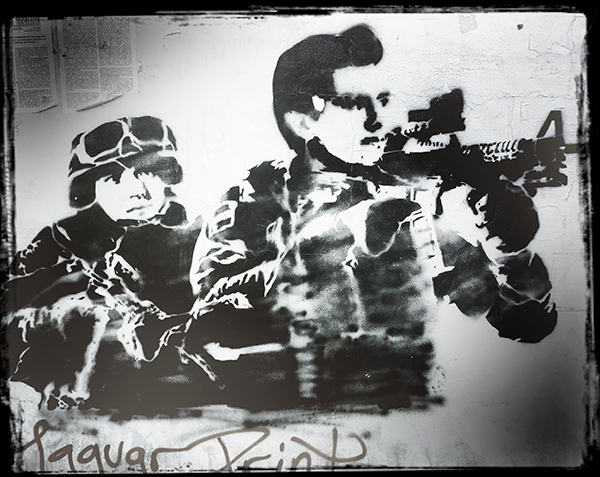

In that sense, I return this time as I always do also with a sense of inadequacy, of lacking either the technology or the skill or both to fill a frame with all that I see and all that I feel. In this image I want the mothers and the children and the dark rooms of dead air in which they live; I want the four Hondurans sleeping on the floor waiting for a chance to sneak into the United States; I want the boy with leukemia being pushed in a wheelchair by his mother between buses on the street because the sidewalks are too narrow to navigate; I want the food – the chicken cooked over a wood fire with tomatoes and chilies, the lentil soup a mother made me before she went to work, the huge plastic glasses of jamaica, the tortas of breaded pork sold on the corner for a $1.50, the smoky, silky mescal that burns and then drains the pain from the body; I want the eyes, dark all of them, bright with laughter, reddened with tears, empty of expectations; I want the nascent beauty of the children and the fading dignity of the grandfathers; I want the conversations – with the taxi driver deported from L.A. who practices his English with me, with the obese sweaty cop and his elegant Belgian shepherd, with the mom who is happy to be pregnant at 35 even though she is without work or husband.

I feel as if I need to make this one picture. I need it to remind me of everything I have done and I do in Oaxaca. I need it to show to people when they ask me why I go there because to explain it with words takes too long.

It is a fanciful desire, to be sure, but still one that nags me.

***

Some other thoughts from the trip:

* Poverty is relative. For a while, I visited a mother and her two kids who lived high on a dry hill in a tin shack. There was no water. The toilet was a hole in the ground. Electricity was boot-legged off a shared power pole. The road was nothing more than rutted trail that ran thick with mud when it rained. Still, I never felt as deep in the Third World at this mother’s house as I did in Oaxaca’s public hospital, where I went one afternoon with one of my favorite children, who had fallen and was visiting a neurologist to see if she had epilepsy.

Outside the hospital, dozens of people camped on the concrete patio, family members visiting hospitalized relatives, or sick people waiting days for appointments. Many slept on cardboard boxes, others used the cheap, synthetic blanks that are so common here to create seating areas that converted to beds at night, and still others had commandeered a row of chairs, stuffed cardboard into the gaps between them and slept on the hard plastic. Buckets of food, scraps of garbage, empty liter bottles of soda and backpacks were everywhere. The faces of the people on the patio bore the weight of lifetime of acceptance of these conditions. This hospital is in one of Oaxaca’s wealthiest neighborhoods. Four blocks from this desperation, moneyed Oaxacans buy Frappuccino’s from Starbucks and shop for clothes in fancy European stores.

* A lot of money for someone who has nothing changes nothing in the long term. My generous friends contributed enough money to help the mother of a boy with leukemia live for months without working, which she needs to do after the live-saving transplant she hopes will come. When I gave her the thick wad of Mexican pesos, her face lifted momentarily in gratitude only to return quickly to its resting visage of resignation, a recognition that no matter how much hardship she endures it cannot guarantee her son’s survival in a society where one’s chances of a long life or an early death are determined at birth. Hers is not a poverty that be bought off with a few thousand pesos.

* Two types of Americans live in Oaxaca. There are those, like the ex-community organizer from California and his wife, an attorney, who use their retirement hours and their professional skills to involve themselves in the community and improve the lives of those who have less than they do. They are in the minority. The majority, most of whom seem to be women, live amongst themselves in an ex-pat bubble, don’t speak Spanish and mix with the locals only when it is time for a festival or an art opening, where they show up dressed in indigenous blouses and skirts and are the first to attack the free food and drinks.

* Intimacy and distance don’t play well together. The closer I get to the families in Oaxaca, the further away I feel when I leave. This is not a new sensation, but on this trip, it grew stronger than ever. I return to a life of comfort, and to a personal calendar that holds fewer and fewer pages, and I leave behind young people with a long future in front of them. For some, the years to come will be good ones of education and family and achievement. For others, there will be decades of labor and sorrow. I wonder how much more of them I will see. I wonder if the goodness I wish for them will ever come to be. I wonder what they will be like at my age, when I am a memory to them, if that.

How was Oaxaca? That’s what everyone asks each time I return. It’s a polite, succinct question and what’s expected in return in the form of an answer is something similar in character, such as: “It was great, thanks.”

How was Oaxaca? That’s what everyone asks each time I return. It’s a polite, succinct question and what’s expected in return in the form of an answer is something similar in character, such as: “It was great, thanks.” OAXACA, Mexico – The late documentary photographer

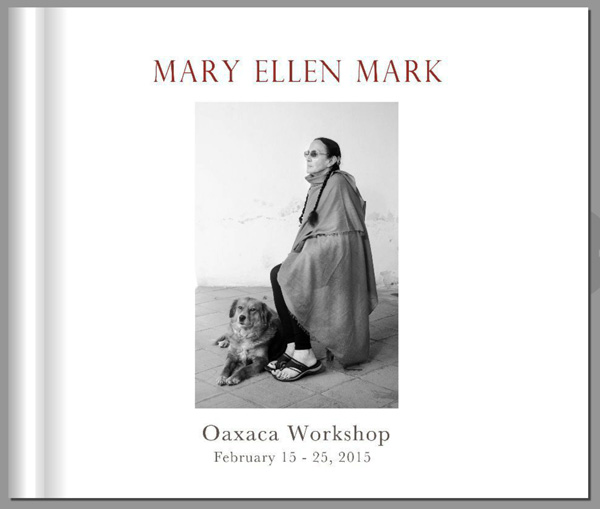

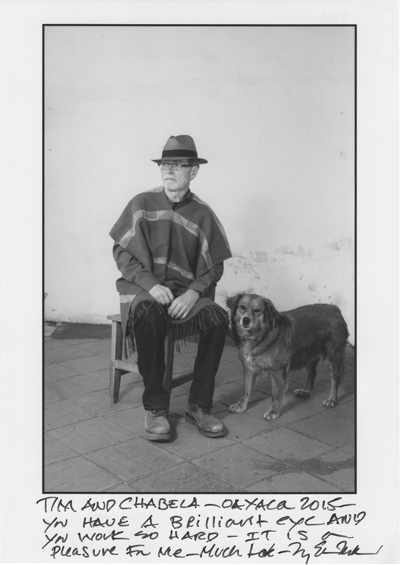

OAXACA, Mexico – The late documentary photographer

There’s nothing pretty about morning in Naco, Arizona. There’s no soft, early light. There’s no lingering cool of the waning night air. There’s no sense of leisurely awakening, no hint of the unfolding promise that a new day offers.

There’s nothing pretty about morning in Naco, Arizona. There’s no soft, early light. There’s no lingering cool of the waning night air. There’s no sense of leisurely awakening, no hint of the unfolding promise that a new day offers.

Before I could say another word, a shoving match broke out between one of the members of the troupe with whom James was traveling and a well-coiffed hipster type who had entered the alleyway with two friends, another man and a woman. Everything about them was sharp and pointy – tight, tailored clothing, hair-dos razored to perfection, well-honed attitudes of superiority. The hipster slid backwards from the shove and dropped in slow motion, looking like the falling Don Draper in the opening sequence of Mad Men. The man in black jettisoned James and the boy and bear-hugged the guy who’d shoved the hipster. It was over.

Before I could say another word, a shoving match broke out between one of the members of the troupe with whom James was traveling and a well-coiffed hipster type who had entered the alleyway with two friends, another man and a woman. Everything about them was sharp and pointy – tight, tailored clothing, hair-dos razored to perfection, well-honed attitudes of superiority. The hipster slid backwards from the shove and dropped in slow motion, looking like the falling Don Draper in the opening sequence of Mad Men. The man in black jettisoned James and the boy and bear-hugged the guy who’d shoved the hipster. It was over. Some of us were in Oaxaca recently. We went at this time of the year because this was when

Some of us were in Oaxaca recently. We went at this time of the year because this was when  Some things I learned in Oaxaca this month:

Some things I learned in Oaxaca this month: