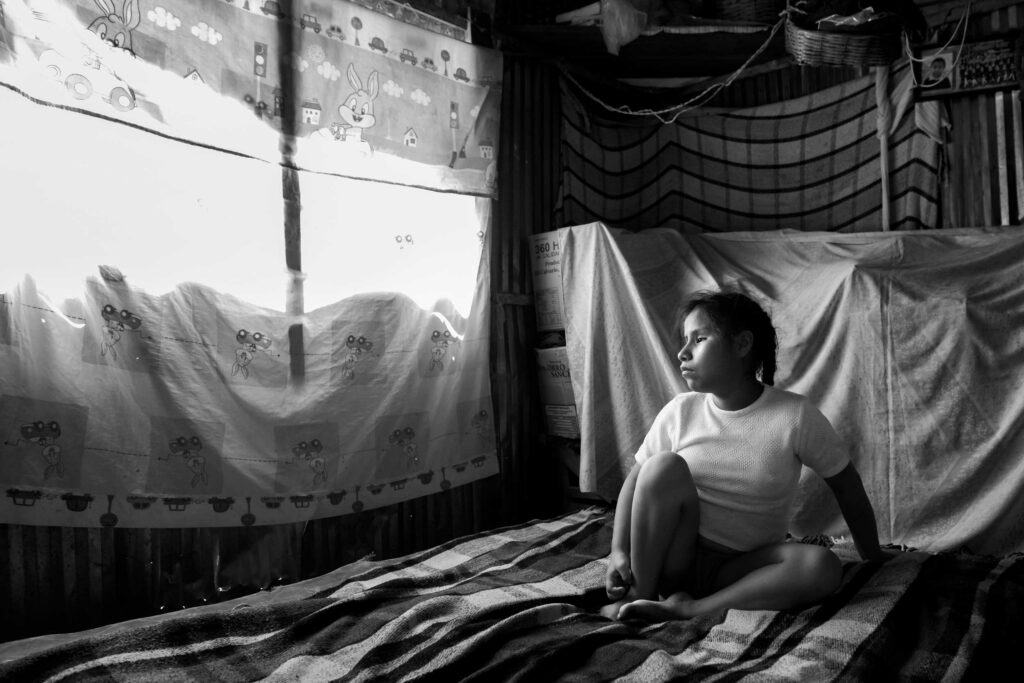

Getzamaní Hernández Rodríguez is 10 years old. She is blind and autistic. She needs special schooling to live an independent life. Without our help, she is condemned to a life of poverty and dependency.

Getzamaní lives with her parents, Edith and Juan Carlos, and her siblings, Nephtali, 11, Ruth, 9 and Elisa, 2, in a house made of tin and cardboard on the outskirts of Oaxaca, Mexico.

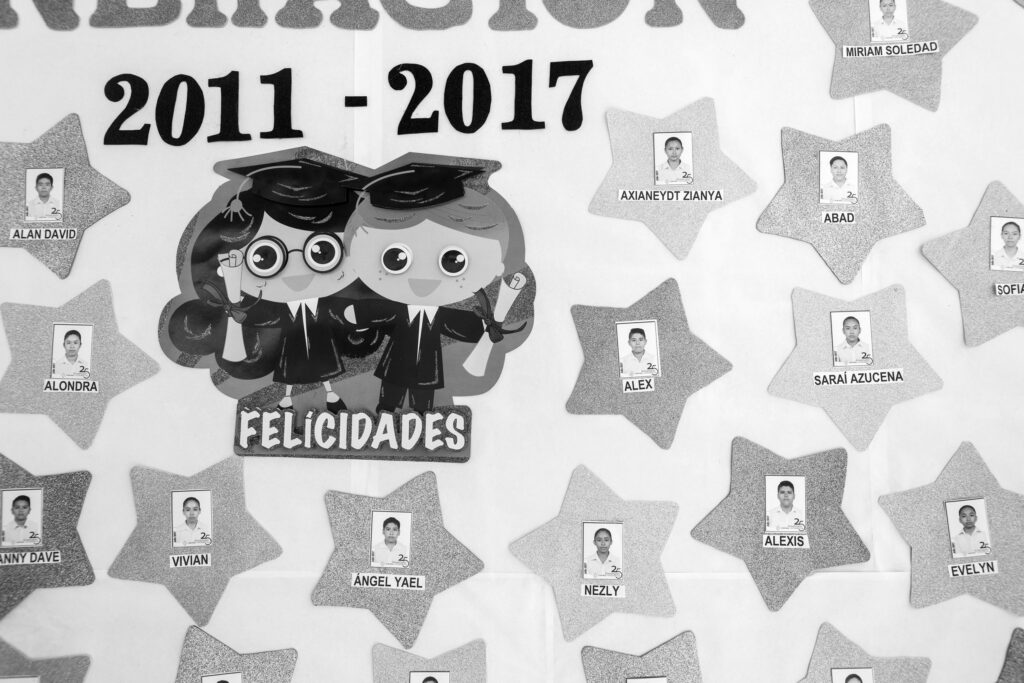

They are poor people in a poor land that does next to nothing to help children like Getzamaní. Only two public schools in the region address the needs of children of children like Getzaman. And they are full. Getzamaní’s mom must take her and the other children — because she can’t leave them home alone – across a sprawling city by moto-taxi and then on foot to a private shelter where classes in Braille and other survival skills are available.

Since Edith can’t work because she spends all day ferrying her children back and forth and waiting for them, the family routinely runs out of money to pay for transportation.

But there is a solution.

Getzamaní can study and receive speech and occupational therapy at home through private teachers. A couple of hundred dollars a month will pay for classes in Braille and other subjects and therapy, the latter to help Getzamaní become more independent – to dress and feed herself and to not have to rely on someone to help her use the bathroom.

If you give $250, you will buy a month of education for Getzamaní. Your generosity will not only change Getzamaní’s life but that of her entire family.

Please help. Give a little or a lot. Whatever you can. One hundred percent of what you give will go directly to the family.

Whatever questions you might have, please message me here or at tim@timporter.com.

I thank you. Getzamaní and her family thank you.