By November last, I was falling behind on my goal of reading (or listening to) one-hundred books in 2024. So, I said to my wife, from now until year’s end I am only choosing books of fewer than two hundred and fifty pages. That’s cheating, she told me.

Fortunately, I ignored her (as she might say I often do), and found myself noshing on a amuse-bouche of titles that were not only delectable but often more tasty than many more portly popular tomes. Among them:

- Orbital, Samantha Harvey (207 pp.)

- The Martian Chronicles, Ray Bradbury (182 pp.)

- The Shadow-Line, Joseph Conrad (192 pp.)

- Eastbound, Maylis de Kerangal (140 pp.)

- The Pole, J.M. Coetzee (166 pp.)

- Passing Nella Larsen (141 pp.)

- If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home, Tim O’Brien (225 pp.)

- Home, Toni Morrison (147 pp.)

- Einstein’s Dreams, Alan Lightman (140 pp.)

- On Chesil Beach Ian McEwan (166 pp.)

Here are the numbers, for those who insist upon them:

- Print – 69

- Audio – 31 (including Barack Obama’s Dreams from my Father and A Promised Land. His august voice alone remedies current discomforts.)

- Did Not Finish (DNF) – 4 (read at least fifty pages)

Once again, thanks to the serendipity of both digital and physical browsing, I found myself delighting in books I might once, limited by a narrower view of the world, never have read. Among them:

- The Safekeep, Yael van der Wouden

- Apeirogon, Colum McCann

- News of the World, Paulette Jiles

- Einstein’s Dreams, Alan Lightman

I have multiples reads from some authors (because why not repeat a good thing?):

Ian McEwan (3), Percival Everett (3), Colm Tóibín (2), Paulette Jiles (2), Jane Harper (2), and among the audio listens for the gym and the trail: Walter Mosely (3), Michael Connelly (3), and Craig Johnson (10).

Finally, ten that I loved, in no particular order:

- Apeirogon, Colum McCann

- Day, Michael Cunningham

- James, Percival Everett

- Flags on the Bayou, James Lee Burke

- The Trees, Percival Everett

- Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, Salman Rushdie

- Legends of the Fall, Jim Harrison

- Eastbound, Maylis de Kerangal

- The Safekeep, Yael van der Wouden

- On Chesil Beach, Ian McEwan

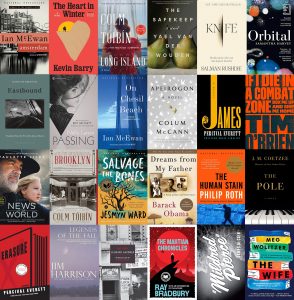

The List, 2024

- Motherless Brooklyn – Jonathan Lethem

- The Brass Verdict – Michael Connelly *

- Nightcrawling – Leila Mottley

- The Women – Kristin Hannah

- This Other Eden – Paul Harding

- The Godfather – Mario Puzo *

- Day – Michael Cunningham

- Devil in a Blue Dress – Walter Mosley *

- Invisible Cities – Italo Calvino

- Amsterdam – Ian McEwan

- Exiles – Jane Harper *

- Lessons – Ian McEwan

- The Lost Man – Jane Harper *

- The Gathering – Anne Enright

- California Fire and Life – Don Winslow *

- Generation Loss – Elizabeth Hand

- Tinkers – Paul Harding

- News of the World – Paulette Jiles *

- The Cold Dish – Craig Johnson

- The Friends of Eddie Coyle – George V. Higgins *

- The World Made Straight – Ron Rash

- Death Without Company – Craig Johnson *

- Enemy Women – Paulette Jiles

- Ordinary Human Failings – Megan Nolan **

- Zero Days – Ruth Ware **

- A Red Death – Walter Mosley *

- Be Mine – Richard Ford

- Sharp Objects – Gillian Flynn *

- Annie Bot – Sierra Greer

- James – Percival Everett

- Kindness Goes Unpunished – Craig Johnson *

- Flags on the Bayou – James Lee Burke

- Until August – Gabriel García Márquez

- City of Dreams – Don Winslow *

- Liliana’s Invincible Summer – Cristina Rivera Garza

- City in Ruins – Don Winslow *

- The Trees – Percival Everett

- Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine – Gail Honeyman

- Another Man’s Moccasins – Craig Johnson *

- The Great Fire – Shirley Hazzard **

- Einstein’s Dreams – Alan Lightman

- White Butterfly – Walter Mosley *

- On Chesil Beach – Ian McEwan

- Brooklyn – Colm Tóibín

- The Dark Horse – Craig Johnson *

- Salvage the Bones – Jesmyn Ward

- The Maltese Falcon – Dashiell Hammett

- The Reformatory – Tananarive Due **

- The Lede – Calvin Trillin

- Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder – Salman Rushdie

- Pet Sematary – Stephen King *

- Junkyard Dogs – Craig Johnson *

- Anxious People – Fredrik Backman

- Between the World and Me – Ta-Nehisi Coates *

- Nightwoods – Charles Frazier

- An American Marriage — Tayari Jones

- Legends of the Fall – Jim Harrison *

- The Human Stain – Philip Roth

- Autocracy Inc. – Anne Applebaum

- Nobody’s Angel – Thomas McGuane *

- In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin – Erik Larson

- Atonement – Ian McEwan

- Hell is Empty – Craig Johnson *

- Speedboat – Renata Adler

- Long Island – Colm Tóibín

- The Nearest Exit – Owen Steinhauer **

- If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home – Tim O’Brien

- Fade Away – Harlan Coben *

- The Almost Moon – Alice Sebold

- The Heart in Winter – Kevin Barry

- Dreams from My Father – Barack Obama *

- Sofrito – Phillippe Diederich

- Passing – Nella Larsen

- Breafast at Tiffany’s – Truman Capote

- The Pole – J.M. Coetzee

- Eastbound – Maylis de Kerangal

- The Wife – Meg Wolitzer

- A Promised Land – Barack Obama *

- Fat City – Leonard Gardner

- The Girls of Slender Means – Muriel Spark *

- The Shadow-Line – Joseph Conrad

- The Overlook, Harry Bosch – Michael Connelly *

- Burn – Peter Heller

- Creation Lake – Rachel Kushner

- 9 Dragons, Harry Bosch – Michael Connelly *

- Pedro Páramo – Juan Rulfo

- Home – Toni Morrison

- A Serpent’s Tooth – Craig Johnson *

- The Marian Chronicles – Ray Bradbury

- Erasure – Percival Everett

- Fortune Favors the Dead – Stephen Spotswood *

- Parade – Rachel Cusk

- Journey Into Fear – Eric Ambler

- Any Other Name – Craig Johnson *

- Orbital – Samantha Harvey

- Dry Bones – Craig Johnson *

- I Remember Nothing – Nora Ephron

- The Invisible Hour – Alice Hoffman

- The Safekeep – Yael van der Wouden

- Mildred Pierce – James M. Cain

* Audio

** Did Not Finish