During the early years of the digital revolution, I wrote a blog that focused on the challenges journalism and newspapers faced in an increasingly digitized society, and the entrenched cultural traditions that inhibited the ability of individual journalists as well as entire institutions to adapt to a changing world that was eroding their relevance and siphoning off their audiences.

During the early years of the digital revolution, I wrote a blog that focused on the challenges journalism and newspapers faced in an increasingly digitized society, and the entrenched cultural traditions that inhibited the ability of individual journalists as well as entire institutions to adapt to a changing world that was eroding their relevance and siphoning off their audiences.

I called the blog First Draft, a nod to the description of journalism as “the first rough draft of history.” The blog coincided with a three-year project I did on newsroom culture and learning for a journalism foundation (which resulted in this slim volume of advice) and served as my exit ramp from the professional world of daily newspapers where I’d lived for a quarter-century.

I left voluntarily and more or less at the top of my game – unlike the many thousands of my former fellow wretches who were riffed or bought out of their careers by collapsing newspaper companies. I was seeking something to fill holes the newspaper couldn’t, especially in those days, when news was defined rigidly, when hidebound hierarchies shaped what was covered and how and by whom, and when middle-age managers like myself saw a future in which deep shadows of uncertainty dulled any glow of promise.

A decade has passed. In that time, I’ve been freelancing wherever I can – and celebrating the hustle and the paltry paychecks as rewards for my liberation from management – and immersing myself more and more in photography, the pursuit that drew me into journalism in the first place.

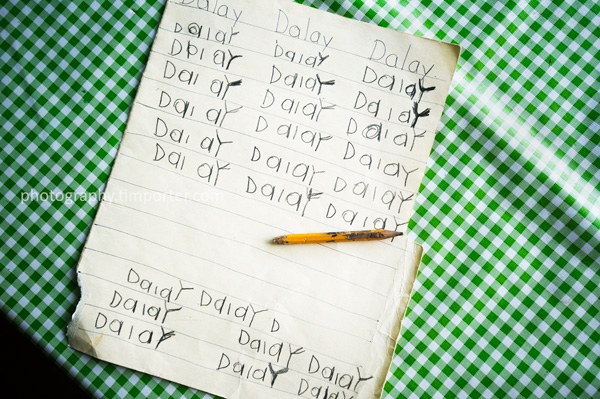

For the last few years, I’ve been photography poor single mothers, repatriated families, children’s shelters and more in Oaxaca, Mexico. It is documentary work and is both intense and, at times, terribly saddening because of its intimacy. It is also immensely satisfying. I feel privileged to be allowed into the lives of these families and angry at the injustice, indifference and corruption that touches them every day. I regularly return home inflamed with the same passion to tell their stories that I felt decades ago in San Francisco during my first years in journalism as an enthusiastic, but unaccomplished photographer.

Therein lies the irony: I am working in what I love the most, photography and journalism, but it is not good work.

Good work? Yes, good work – “work of expert quality that benefits the broader society.” In other words, “good work” is at once personally satisfying and socially beneficial. The concept was the focus of a book (Good Work, When Excellence and Ethics Meet) by three Stanford psychologists that explored the challenges and rewards of doing “good work” in various fields, including journalism. The authors found a direct connection between the ability to do good work and self-fulfillment.

“Doing good work feels good,” they write. “Few things in life are as enjoyable as when we concentrate on a difficult task, using all our skills, knowing what has to be done.” … Good work is “something that allows the full expression of what is best in us.”

I’m not going to go further into the book, but it is well worth reading by anyone who has more than a passing interest in the current collision of values in what is now lumped under the term “the news media” and also between journalists who wish to adhere to the profession’s traditions of truth, fairness and, hopefully, justice, and the politicians and government institutions on which they report. In other words, in a world of lies and liars, how much currency does the truth retain?

For now, though, I am focusing on “good work” in a more selfish way: What I need to do to upgrade my documentary photography in Mexico from work to “good work.”

What I lack the most, I believe, is the opportunity to publish. An image that hides in a computer file is not “good work.” Stories that languish untold are not “good work.” A reporter who doesn’t empty her notebook or a photographer who does little more than fill his archives is not doing “good work.”

That’s what organized journalism provides, not only the opportunity to publish but the obligation to. Journalism does not happen in a vacuum. It is not just the academic, but also the journalist who must publish less the work perish. If good work, as Damon wrote, “allows the full expression” of the best inside each of us, then I am falling short because I have always expressed myself publicly.

In this context, I miss the newsroom. I have yet to accomplish alone what I did with other journalists, imperfect as it was. I miss the sense of purpose journalism provides. I miss the camaraderie. I miss the demands of deadlines. I miss waking each day with the belief, however misplaced or self-delusional it might be at times, that the day’s work ahead will matter to someone and perhaps make the world a more informed, more just or perhaps simply more functional place.

That desire is a universal characteristic among good journalists. In June 2004, after interviewing dozens of journalists for a project, I wrote that they possessed a common goodness: “ … the deep, abiding desire … to do good journalistic work. They believed to a person that the purpose of journalism is to provide, at the least, information and, at its best, knowledge to their fellow citizens with the purpose of bettering society.”

When these journalists could overcome “the oppressive troika of tradition, convention and production that combine to prevent most newspaper journalists from realizing these good intentions on a frequent basis” they achieved that purpose.

One reason I left the newsroom was that felt I could not otherwise escape that tyranny. What I have since discovered is just as there can be too much tyranny for some people there can be too much liberty for others, of which I am one.

I work better with structure. I work better on deadline. I work better under pressure. I need these things to do “good work.”

All that I had when I was younger even though I was less skilled, less accomplished and more full of myself. However, and I can say this now with the clarified vision of hindsight, I didn’t truly appreciate the work, the people and the basic purpose of journalism until I had it no more.

I want it back. Or as much of it as I can get back at my age. But how? I am too old to be hired somewhere, too experienced to be naïve and to hope to begin anew, and I carry far too much baggage filled with failures and (fewer) successes to share company with those who view reporting and photography as “content” designed to drive clicks.

You might think, given my age, that what I miss is not journalism, but my youth. That’s a reasonable assumption, but I can assure you that my longing for good work is not the waning pang of an aging heart. I would not wish my younger days on anyone (although I admit that certain less salubrious traits of those years served me well in newspapers, which at the time celebrated the aberrant as long as you could hit a deadline.)

No, what I want reflects a desire that only comes with age – the opportunity to do work that encompasses what I’ve learned over the years, that utilizes the skills I’ve acquired and forces me to challenge myself and confront the truths of the world around me. Good work.

Making this happen will be my greatest challenge.

It is unsettling to me, someone who has spent the better part of his doing one form of journalism or another, that the brazen embrace of The Big Lie by politicians has become so prevalent that those of us who prefer facts over fiction find ourselves making a case for the importance of truth.

It is unsettling to me, someone who has spent the better part of his doing one form of journalism or another, that the brazen embrace of The Big Lie by politicians has become so prevalent that those of us who prefer facts over fiction find ourselves making a case for the importance of truth.

As much as I don’t like politics, I confess that I do like politicians – in person, at least. One on one, pols of various stripes are among the smartest, most engaging people I’ve met while doing journalism. They’re articulate, their words are pointed, and they share the same off-center sense of humor that is found in most newsrooms.

As much as I don’t like politics, I confess that I do like politicians – in person, at least. One on one, pols of various stripes are among the smartest, most engaging people I’ve met while doing journalism. They’re articulate, their words are pointed, and they share the same off-center sense of humor that is found in most newsrooms. The

The