All of my adult professional life I have been a journalist of some sort or another and with varying degrees of quality.

All of my adult professional life I have been a journalist of some sort or another and with varying degrees of quality.

Through most of these now 40 years I adhered to the canon of the trade – objectivity over bias, fairness over partisanship and fact over belief. In the last decade, however, my views changed, especially during the several years in which I wrote a blog (First Draft) about the constraints these core principles imposed on a profession whose defining practices were under assault by a digitally empowered audience and other disruptive technological and economic forces.

I came to see how the he-said-she-said definition of objectivity favored stenography over narrative and defined a “story” as something that always had two sides, regardless of how ludicrous, shallow or blatantly false one of those sides might be.

I stuck with the concept of fairness longer, but eventually it, too, was eroded when I began to consider the impact a simple phrase such as “in all fairness.” In a story, for example, about immigrants forced into indentured servitude in a sweatshop, must a journalist “in all fairness” give voice as well to the person who has economically enslaved these women? When Donald Trump bleats about Muslims or Mexican rapists, must a reporter “in all fairness” allow his spokesperson to rationalize such racist remarks? I once thought so, but I no longer do.

Of those canonical components of traditional journalism, what for me persists is the principle that facts matter more than belief (or opinion, if you will). Underlying this principle is a foundational layer of logic that things are either true or they are not and that the evidence of these truths can be found in facts.

I realize, of course, that the retail value of fact in the realm of politics and much of the rest of public discourse in the U.S. has fallen to nearly zero, but following the advice of my wise mother I am not going to jump off the bridge just because the other kids are doing so. I cling, comfortably, to the notion that facts enable those of us who care about such things to define what is true and what is not.

Here is where my problem lies.

I have come across, quite by accident, perhaps the best story of my journalistic life and I don’t know how to tell it because the facts of the story are not only elusive, but I think they will never be known (at least not to me).

I believe a terrible injustice is being done, but I can’t prove it.

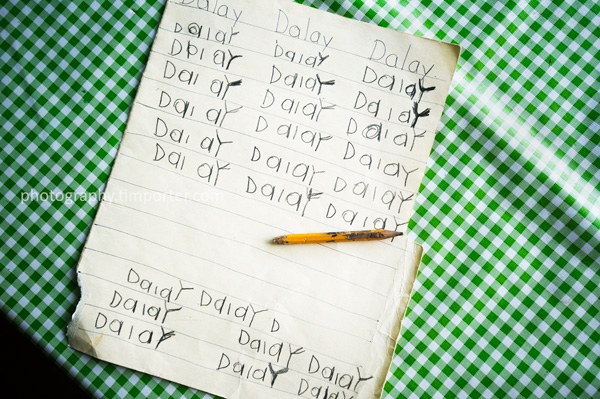

I believe a powerful, politically connected person or persons have pulled enough levers to imprison a woman who less than two years ago was honored by the Dalai Lama for her compassionate work with poor children, but I can’t prove it.

I don’t believe the grave charges that have been compiled against this person and her family, but I can’t prove that what they are accused of doing never happened.

I believe I know the truth in this case, but I can’t prove it.

What is more important: what I believe to be true or what can be defined by the few, verifiable facts that exist, which is very little? Is it more ethical to write about what I believe to be a terrible injustice and risk being proven wrong when someday perhaps more contradictory facts emerge or to stay silent and let others who are more partisan champion her case?

I feel somewhat embarrassed to be even asking these questions because what moral center I’ve managed to keep intact over these years is shouting at me to write what I believe. Countering that cry, though, is the cautious reasoning of my remaining journalistic mind, which argues that anything is possible, that even good people do bad things and that is why stories must be told from the facts rather than from beliefs.

Truthfully, I am not looking to anyone else for an answer. It will come – it has to come – from me. Voicing this dilemma, though, enables me to better parse its components. Stay tuned.