War inflicts two types of violence: immediate and protracted. The former arrives as a bullet or a bomb, come and gone in an instant; the latter, though, lingers, suppressing the defeated through a deliberate, ongoing degradation of individual and civic life – control of movement and expression, fear of arrest and disappearance, lack of food, medicine and other necessities. It is intended to grind the body and the soul into complete submission.

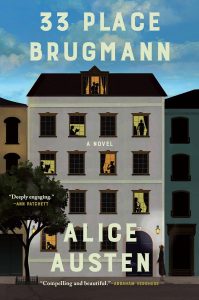

As “33 Place Brugmann” opens in August 1939, the residents of this eponymously named apartment building in Brussels sense the coming storm. With the Great War concluded only twenty years earlier, Germany is once again ascendant and militarized. More than invasion, which seems inevitable, the Belgians, especially those who are Jewish, fear occupation.

The tenants are a diverse group, among them: an architect and his precocious teenage daughter, Charlotte (who is chief among the characters); an art dealer who is Jewish; a retired army officer; a Russian refugee; and the building supervisor, who favors the Nazis. As the Germans approach, the art dealer and his family flee to Scotland (but do not escape the reach of the war), while the others confront the daily indignities of life under the eyes of the Gestapo.

The beauty of Austen’s storytelling is that is doesn’t descend into tropes. It is multi-dimensional. While, yes, anxiety and paranoia are endemic within 33 Place Brugmann, there are also celebration of small victories, recognition of the restorative power of art, and presence of the persistent, simmering belief – growing as the years pass – that survival is possible.

“33 Place Brugmann” made me think of Anthony Doerr’s “All the Light We Cannot See” (2017), the story of another father-daughter family caught in the same war. In comparison, Doerr’s book is richer and more complex, but that is not to take anything away from “33 Place Brugmann,” which is equally human and equally effective at capturing the long violence of war.