A few days ago the Wall Street Journal published a lengthy story about the ominous criminal, political and social conditions in Mexico that have combined to degrade civil society in many parts of the country to the brink of public disorder.

Fueling this collapse are two evils — the ravenous appetite of the narco cartels for control of the border, of law enforcement and of the proverbial hearts and minds of Mexico’s impoverished citizens; and the endemic, ubiquitous and persistent corruption of government on all levels.

The Journal piece focused on the implications for the United States should the rule of law fail in Mexico. It quoted a high-ranking official in the country’s current ruling party, the PAN:

“The Mexican state is in danger. We are not yet a failed state, but if we don’t take action soon, we will become one very soon.”

For me, it’s more personal. I have good friends — Mexicans and Americans — who live there. I have a house in Oaxaca, Mexico’s most beautiful state and also its poorest. I have seen the country’s working people, through resilient desire and endless effort, carve out good lives for themselves amid a system that favors the wealthy, the connected and the corrupt. And, sadly, I have witnessed well-off people I considered friends express disdain for the poor and for the creation of a society of laws. They are, after all, the beneficiaries of the current system.

I don’t cry easily. The scar tissue laid on during 20 years of daily journalism usually keeps the tears in check. But these days Mexico makes me cry.

In the fall of 2006 I stood in the zócalo, the main square, of Oaxaca – a place I love, where I got married, where I built a house on the far end of a dirt road – and watched a battered TV play a video of the day state police rousted striking public school teachers from the square. I watched the rise and fall of batons on makeshift shelters. I saw the march of heavy boots through darkened streets. Fires burned. Rocks flew. The camera shook. Above all, I heard the sound of helicopters, which police used to fling canisters of tear gas into the crowds below.

I cried right there as the video played. A woman next to me, dressed in the traditional apron of a southern Mexican housewife, saw me, an aging gringo journalist laden with camera gear, and said, “Que triste. Que triste.” How sad. How sad.

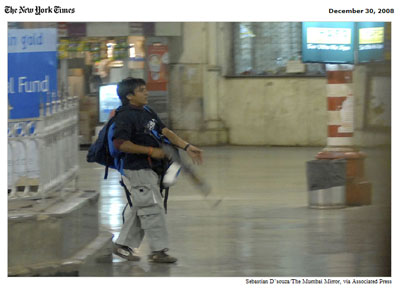

A few days later, local thugs — some say off-duty cops — opened fire on a protest march, killing freelance American journalist Brad Will. (Here’s a picture — not mine — of the shooting.)

The resulting international outrage — far beyond any that accompanied the earlier deaths of dozens of Oaxacans — prompted the federal government to send troops into the city restore order.

More than two years later, nothing has changed for the better in Oaxaca. The economy, highly dependent on tourism, has yet to recover. The governor who attacked the striking teachers remains in power. The leaders of the strike are jailed. The killers of Brad Will are free. (The photo at the top of the post is from an anniversary march in Oaxaca’s main square two years after the 2006 attacks.)

Multiply this one incident — a strike, a shooting, a disregard by the authorities for even the facade of justice — throughout the country and amplify it along the drug-trafficking lanes in the border cities and you begin to get grasp of the severity of the challenges Mexico faces. Here’s one fact: 6,000 people were killed in Mexico last year in drug-related violence. The U.S. dead in Iraq for six years of war is 4,200.

Perhaps you wonder why you should care about what happens in Mexico. After all, aren’t the beaches in Baja still beautiful and the pina coladas in Cancun just as tasty? De veras, they are. But Mexico is much more than an American playground.

First, it is also, as the Journal points out, the largest U.S. trading partner and with our economy already on life support we don’t need to lose our best customer.

Second, if you think having more than 4 million undocumented Mexican immigrants living in the United States is troublesome, then imagine the immigration pressure on the border should the Mexican government collapse. Says the Journal:

“It has 100 million people on the southern doorstep of the U.S., meaning any serious instability would flood the U.S. with refugees.”

Finally, there is morality. What is happening in Mexico is simply wrong. It is wrong to oppress the poor so the wealthy can prosper. It is wrong to deny people jobs because they belong to an opposing political party. It is wrong to glorify crime and drug use. And, it is wrong to kill journalists. (Read this report, or this one, or this one from the Committee to Protect Journalists.)

Poor Mexico. I cry for you. I wish I could do more.

*How Not to Get Shot in a War Zone: Advice from conflict photographer Teru Kuwayama.

*How Not to Get Shot in a War Zone: Advice from conflict photographer Teru Kuwayama.

* The Mexican Suitcase: The I

* The Mexican Suitcase: The I

Fran was a man of immense visual talent, but what made him such an accomplished photographer were his patience, gentility and humor, qualities that enabled him to insert himself (and his camera) into the lives of his subjects so seamlessly.

Fran was a man of immense visual talent, but what made him such an accomplished photographer were his patience, gentility and humor, qualities that enabled him to insert himself (and his camera) into the lives of his subjects so seamlessly. Last year was a tough year for journalism (and many other professions). Newspapers, a

Last year was a tough year for journalism (and many other professions). Newspapers, a

Each month for

Each month for

Anyone who has worked in media knows the end product — magazine, newspaper, film — represents a series of choices and decisions made by individual creators, the team as a whole and, increasingly in films, the audience. (And, of course, web-based media like

Anyone who has worked in media knows the end product — magazine, newspaper, film — represents a series of choices and decisions made by individual creators, the team as a whole and, increasingly in films, the audience. (And, of course, web-based media like  We shot for about 30 minutes in the booth, including a sequence in which she acted out some scenes (left).

We shot for about 30 minutes in the booth, including a sequence in which she acted out some scenes (left).

As much as I don’t like politics, I confess that I do like politicians – in person, at least. One on one, pols of various stripes are among the smartest, most engaging people I’ve met while doing journalism. They’re articulate, their words are pointed, and they share the same off-center sense of humor that is found in most newsrooms.

As much as I don’t like politics, I confess that I do like politicians – in person, at least. One on one, pols of various stripes are among the smartest, most engaging people I’ve met while doing journalism. They’re articulate, their words are pointed, and they share the same off-center sense of humor that is found in most newsrooms.