As a man of the Anglo-Saxon-mongrel variety, I never had to worry about identity. Sure, in the working-class, industrial city where I grew up we kids would ask each other What are you? But whether we answered Irish or Italian or Polish there was never any doubt what we were: White.

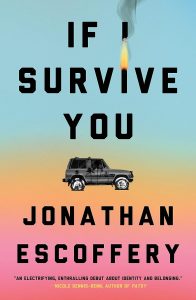

Such certainty eludes Trelawny, the protagonist of “If I Survive You.” The son of Jamaican immigrants he traverses childhood to adulthood afloat in a sea of swirling colors and cultures. In a Miami high school, he is too brown to hang with the Blacks, too mono-lingual to hablar with the Latinos, and too Yankee – meaning adverse to speaking the island patois – to other Jamaicans. In a Midwest college, amid a cloud of pink-toned classmates, he is “unquestionably Black.”

His older brother, Delano, tells him: “You’re Black, Trelawny. In Jamaica we weren’t, but here we are. There’s a ‘one-drop’ rule.” But then a white co-worker, after making a racist remark, says to Trelawny: “What do you care? You’re not Black. You’re Jamaican.” Suddenly, thinks Trelawny, “Black Americans are the only Blacks. Blacker than Africans. Black in the (lowered voice) bad way.”

Escoffery places Trelawny’s personal journey amid a prism of stories about the searches of life: Cukie, a friend of Trelawny’s searches for his father, only to find that truth can lead to betrayal; a tragedy gives Delano one more chance to follow the ambition he abandoned for more pragmatic pursuits; a mysterious middle-aged woman, smitten with love, wishes to weasel her way into the old-folks home where Trelawny works.

Again and again, “If I Survive You” returns to Trelawny’s relationship with his father, a general contractor who dotes on Delano and sees his younger son as weak and adrift, an affront to his immigrant mindset that places survival about all else.

Trelawny does indeed wander. Booted from father’s house, he moves into his car, and uses the perception that “every light brown thing in Miami is exotic” to entice female tourists with “colonial desires” to take him back to their hotels, where he will have a bed for the night. He cycles through jobs both tedious and perverse (punching a woman in the face for an art project, watching an affluent white couple have sex). Through it all, he seeks to make peace with himself and, at least inwardly, with his father.

The New York Times called Escoffery “a gifted, sure-footed storyteller, with a command of evocative language and perfectly chosen details.” Dead-on right. There are not many pages in “If I Survive You” that lack a savory turn of phrase or a piquant observation, many of them about Miami and its environs, an extra treat for those of us who, rightly or wrongly, see South Florida as the slightly off-kilter uncle in the American family.