I am not sure what came first in my life, photography or journalism, but both influenced me greatly as a young man.

While I was in college, I worked in the darkroom at UC Extension in San Francisco, where my fellow lab rats were mostly students at the San Francisco Art Institute. In our spare time, and there was plenty of that after the day’s chemicals were mixed, they taught me to print deep blacks and luminous whites on rich, expensive sheets of Agfa paper and instilled in me the belief that each of us can see the world in an unique manner if we only look long and hard enough.

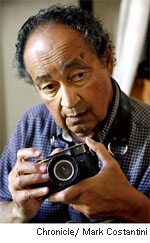

After work, I studied photojournalism, which had its own, and very different, definitions of photography. It focused on people, it told stories, it exposed injustice, it was active and, my favorite teacher, Fran Ortiz, used to say, it was done best close in. If your pictures aren’t good enough, he’d preach, get closer.

I took all those messages to heart and, as most students do, made photographs that imitated the best photographers of both worlds. The artist in me photographed empty beds, their white sheets lit by sunlight from open windows, and then spent hours making one print in the darkroom. The photojournalist in me chased news — the trial of kidnapped newspaper heiress Patty Hearst — then rushed to UPI where I developed and dried the film (with a hair dryer!) in two minutes, made a one-minute print and put it on the wire, all for glory and $15 a shot.

Eventually, the journalism won out and by the time I was ready to leave college more than anything I wanted to be a newspaper photographer. That was not to be, though, for several reasons. I had talent, but I lacked confidence in my work and doubted my instincts, a bad combination in an industry that rewards drive and ambition (as well as talent), so when the photo editor of a big San Francisco paper suggested I try another field I was crushed.

I moved on to a job as a reporter (who did some photography) and then into a long period of editing. I did well, ran a couple of newsrooms and got to be waist deep in some of the biggest local news of my generation. Fast forward a few years past the Internet boom and there I was successful and skilled in many things except that which I always wanted to do — photography.

About that time, when I was finishing a book on newspapers and facing an intersection on the road ahead, my wife gave me a little digital camera. That gift changed my life. I began shooting and shooting, amazed at the possibilities of digital but also frustrated by the camera’s shortcomings, so I bought my first DSLR, a Nikon D70s. Quite serendipitously, a friend co-founded Marin Magazine about the same time and asked me to be involved.

Suddenly, I became a photographer (who does some writing). The learning curve was steep. I knew the basics, I had a decent eye, I could think on my feet and I could navigate a story like a journalist, but I knew little about lighting, Photoshop and the demands of magazine photography, which are more about editorial style than the raw truth-telling of photojournalism.

But I’ve learned. I’m better. I can light just about anything, can make the software do pretty much what I want, can walk into most any situation and come out with something to publish, and can make almost anyone look good.

I consider those the basics — the things any photographer needs to make “their” photos, “their” meaning the clients, whether a magazine, a baker or a university, all of which I’ve shot for this month.

What I want now is a vision — the thing I need to make “my” photos.

Yesterday, I posted a some links to art photographers I like (see Grab Shots: Get Out of the Rut). When I see this sort of work, I see photographers shooting for and creating images for themselves, not for others. Don’t misunderstand, I am thrilled by the opportunity to make “their” photos — few people get the sort of second chance I’ve been given — but as much as I wanted to be a newspaper shooter when I was younger I now, much older, want to find photography that is “mine.”

Do I know what “mine” is? No, not yet, but there is a kernel of it in this picture, which I made for Marin Magazine to illustrate a story on school costs. The magazine used a different frame, one a bit more flattering to the girl, the child of a local parent. That was theirs.

This one is mine.

Fran was a man of immense visual talent, but what made him such an accomplished photographer were his patience, gentility and humor, qualities that enabled him to insert himself (and his camera) into the lives of his subjects so seamlessly.

Fran was a man of immense visual talent, but what made him such an accomplished photographer were his patience, gentility and humor, qualities that enabled him to insert himself (and his camera) into the lives of his subjects so seamlessly.