OAXACA, Mexico – The late documentary photographer Mary Ellen Mark had a 20-year love affair with Oaxaca, an affection she demonstrated in the many indelible images she made here of children, animals and regional rituals, but also in the passion she imparted and instilled in the hundreds of amateur and professionals who attended her biannual workshops here.

OAXACA, Mexico – The late documentary photographer Mary Ellen Mark had a 20-year love affair with Oaxaca, an affection she demonstrated in the many indelible images she made here of children, animals and regional rituals, but also in the passion she imparted and instilled in the hundreds of amateur and professionals who attended her biannual workshops here.

After Mary Ellen died in the spring of 2015, several of us who have become friends through knowing her and working with her in Oaxaca decided to return to Mexico together each year to honor Mary Ellen and continue the projects she had helped us shape.

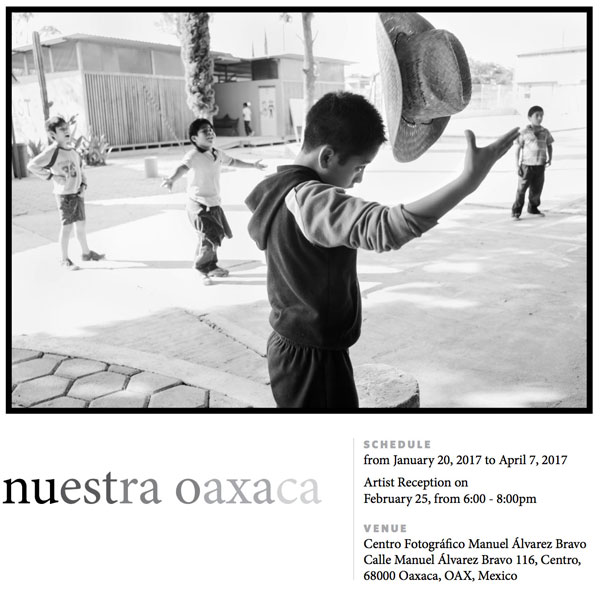

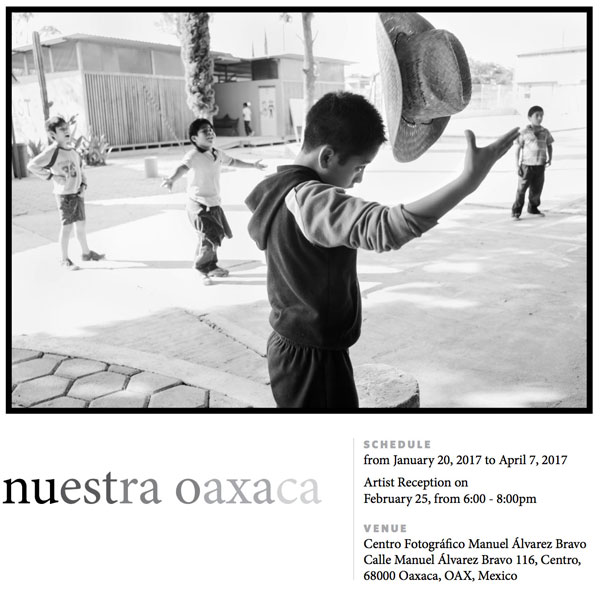

Knowing of our desire to keep Mary Ellen’s Oaxaca spirit alive, the Centro Fotográfico Manuel Álvarez Bravo (where Mary Ellen had convened her workshops) invited seven of us to show our images from Oaxaca. It was a bittersweet invitation – on the one hand an honor to participate in an exhibition at Álvarez Bravo, on the other another reminder of how much each of us miss Mary Ellen, as a teacher, as an editor, as a friend.

After much planning by the staff of Álvarez Bravo (and much patience and tolerance by its director, Adriana Chávez, for our lack of understanding of the metric system and constant mangling of the Spanish language), the show opens this Friday, Jan. 20, and will feature photographs by Björn Árnason (Iceland); Ina Bernstein, Chae Kihn and Jody Watkins (New York); and Lori Barra, James Carbone and me (California).

The evening of the opening there will be a reception at 7 p.m. (I will be there and I hope my friends in Oaxaca can come.) On Feb. 25 from 6 to 8 p.m. Álvarez Bravo will graciously host an event with all seven us.

Below, in English and in Spanish, is the introductory text to the exhibit, as well as a gallery of the photos I have in the show.

Exhibition Introduction: Our Oaxaca

Mary Ellen Mark brought us together. Most of us came to Oaxaca because of her. Through her we became friends. Because of her we became better photographers. With her in mind, we come back – to pursue the work we started here, to nurture the relationships we’ve made with local mothers and fathers and children, to become the photographers she believed we could be, to honor her passion and, perhaps, to find hope and inspiration in it.

More than anything else, Mary Ellen believed in the potency of the singular image. “I like a picture to stand out individually, to work on its own,” she said. “… It’s hard. If you get a couple of good pictures a year, you’re doing very well. It’s hard to get a great picture. Really hard. The more you work at it, the more you realize how hard it is.”

As a photographer, Mary Ellen embraced relentless authenticity. As a friend, she wrapped us in generosity. As a teacher, she demanded much and encouraged even more.

Mary Ellen held her students to the same lofty standards by which she lived. Two years before her death in 2015, she told an interviewer who had asked how her photography had evolved during her 40-year career. “I’m not sure it has changed that much,” she answered. “… I’m still just trying to make powerful and truthful photographs — great photographs. Perhaps my standards are higher. I’m less satisfied with what I do. I want to go further. Reach further.”

Go further. Seek truth. Be honest. These were Mary Ellen’s qualities – as a photographer and as a person – and these are the characteristics by which she judged her work and to which she urged us to aspire.

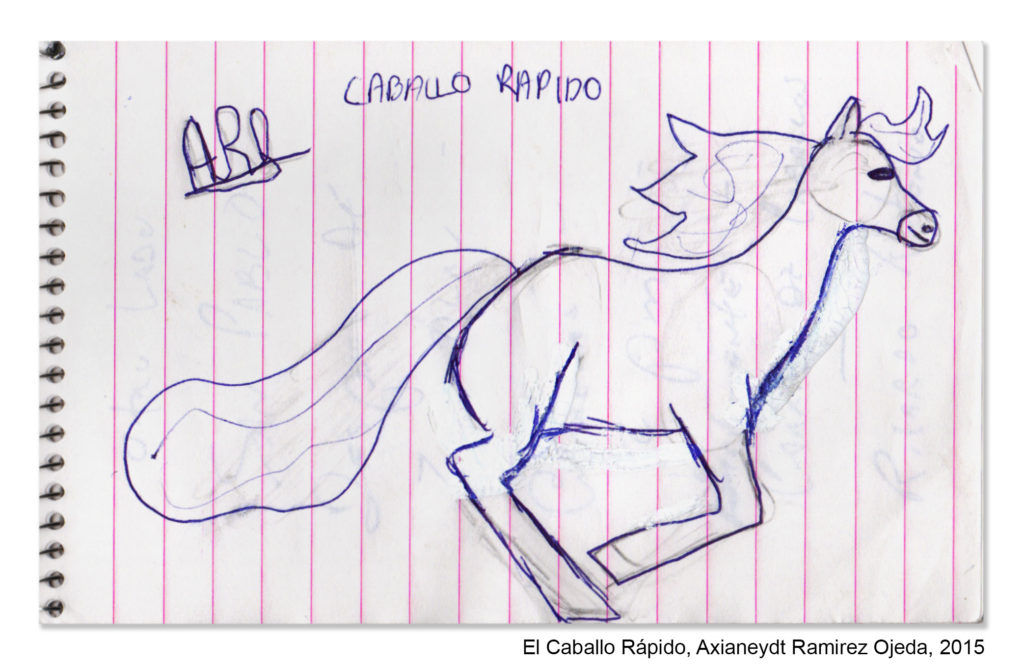

Some of us are professional photographers, some are not. Some of us have been photographing the same families for a decade or more, some are drawn to the spontaneity of the streets. Some of us use the camera to document, some of us prefer to interpret. All of us are grateful to have known Mary Ellen, to have worked with her and to have been counted among her friends. In our work, we can only hope to emulate her, each of us in our own way.

Mary Ellen once said, “Photograph the world as it is. Nothing’s more interesting than reality.” These photographs are our reality, our Oaxaca.

***

Introdución a la Exposición: Nuestra Oaxaca

Mary Ellen Mark nos unió. Ella fue la razón por la que llegamos a Oaxaca. A través de ella, nos hicimos amigos. Debido a ella, nos convertimos en mejores fotógrafos. Pensando en ella, regresamos – para seguir las obras que empezamos aquí, para alimentar las relaciones que hemos formado con madres, padres y niños oaxaqueños, para hacernos los fotógrafos que ella creía que podríamos ser, para honrar su pasión y, quizás, encontrar esperanza e inspiración en esta.

Más que nada, Mary Ellen creía en el poder de la imagen singular. “Me gusta una imagen que resalte individualmente, que surta efecto sola,” dijo ella. “ … Es difícil. Si sacas un par de buenas fotos cada año, estas haciendo muy bien. Es difícil sacar una gran foto. Muy difícil. Cuanto más trabajas en ello, más te das cuenta de lo difícil que es.”

Como fotógrafa, Mary Ellen abrazaba la autenticidad implacable. Como amiga, nos envolvía en la generosidad. Como maestra, exigía mucho y animaba aún más.

Mary Ellen insistía en que sus alumnos se adhirieran a los mismos estándares altos en los que ella se mantenía. Dos años antes de su muerte en 2015, le dijo a un entrevistador que le había preguntado a ella como su fotografía se había desarrollado durante su carrera de 40 años: “No estoy segura de que haya cambiado mucho. … Solo sigo tratando de hacer fotos que sean potentes y verídicas – grandes fotos. Quizás mis estándares sean mas altos. Estoy menos satisfecha (ahora) con lo que hago. Quiero ir más allá. Alcanzar más allá.”

Vaya más allá. Busque la verdad. Sea honesto. Estos eran los atributos de Mary Ellen – como una fotógrafa y como un ser humano – y estas son las características por las cuales ella juzgaba su obra y a las cuales noså urgía aspirar.

Algunos de nosotros somos fotógrafos profesionales, otros no los somos. Algunos de nosotros hemos estado sacando fotos de las mismas familias por más de una década, otros estamos atraídos por la espontaneidad de las calles. Algunos de nosotros usamos la cámara para documentar, otros preferimos interpretar. Todos nosotros estamos agradecidos de haber conocido a Mary Ellen, de haber trabajado con ella y de haber estado entre sus amigos. En nuestra obra, solamente podemos esperar emular a ella, cada uno en su propia estilo.

Mary Ellen dijo una vez,” Fotografíe el mundo como es. Nada es más interesante que la realidad. Estas imágenes son nuestra realidad, nuestra Oaxaca.

OAXACA, Mexico – The late documentary photographer

OAXACA, Mexico – The late documentary photographer