In my quest this year to reach a three-digit number of books read, I’ve reduced the page count, favoring of late slim titles.

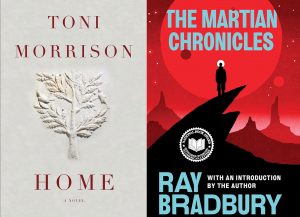

This less-is-more strategy has produced an unexpected benefit: an upgrade in quality. In recent weeks I’ve been entertained and enlightened by J.M. Coetzee, Meg Wolitzer, Joseph Conrad, Juan Rulfo, and, now, Toni Morrison and Ray Bradbury.

***

“Home” is the more soulful of these two titles. It tells the story of Frank Money, a young man just mustered out of the Army after a stint amid the slaughter of the Korean War, and his younger sister, Cee, a survivor of horrific abuse inflicted by an eugenics-obsessed doctor. Both carry secrets, one shared since childhood when they saw a band of white men burying a Black body in a field, and one Frank bears alone, a scarring memory brought home from war.

As they struggle to reunite in their rural Southern town, they must muck through the sheen of post-war racism that oozes across the country, subtle in some areas, but flagrant in the sibling’s native ground. Morrison, as she always does, infuses “Home” with humanity, and lets the narrative unfold from there.

Although the underlying themes are heavy, the storytelling is not. The dialogue is rich and uttered by an array of characters, some hateful, others delightful, all interesting. Well worth reading.

***

“The Martian Chronicles” – which I never read until now – imagines the colonization of the fourth planet from the sun by the denizens of the third planet. The story begins in the year 2030 when Earthlings once again face the existential threat of nuclear war.

Told through a series of short, anecdotal stories connected by context but distinct by time and subject, “The Martian Chronicles” is a cautionary tale. It warns, with both force and humor (if one can laugh at the fate of the world) that toxic culture is not detoxified by being transplanted in a more benign environment, but rather tends to infect its new host, as the Martians find out to their detriment.

Writing amid the geo-political pall of post-war America, Bradbury uses the anthems of the times – the red scare, the nuclear scare, the hegemony of the U.S., the rising nationalistic censorship of art, dissent, and differing points-of-view – to make his point: we are a flawed species and not much good can come of us. Again, serious stuff, but addressed with deft, irony and sarcasm.

The book is full of surprises even as it wends its way toward one of several imaginable endings – a Door #1, #2, or #3 situation. No matter which door you choose, what lies beyond should please you.