A writer dies, her book is not done, her husband writes the final chapter

There is no more tenuous concept than time. Hours, days and years are inventions of man, an application of accounting and order to a life whose beginning is mysterious but whose conclusion is both clear and capricious.

Time, as a mechanism, constructs a façade of stability behind which extends a void that defies definition. What we call “today” is a random assortment of instances, each so infinitesimally transitory that we can neither immerse ourselves in them nor extract from them any indelible depth of experience. Tomorrow is perpetually beyond reach, unattainable, because it exists only in our heads. As soon as the rising sun cracks the horizon, tomorrow disappears under the onslaught of today. Our brains are wired for now; every instant of consciousness occurs today.

What remains is the past, a grand mausoleum of dismembered memories. This unkempt charnel house of fading images, distant conversations, and joys and pains exaggerated or tempered by time tempts examination, especially by writers and others who seek to make sense in their lives. But the past is not a single, definable entity of what was. The past consists of only what we remember, and even that is unique in quantity and clarity for each of us.

“The unexamined life is not worth living,” said the Greek. But what of the unexamined past? Should it be disinterred?

***

When Mary Ann Hogan and I met we were journalists, she a reporter for a big newspaper, and I the editor of a smaller one. I was arrogant, aggressive, and inflated with self-worth; she was everything that was the opposite: sweet, lovely, and brimming with talent.

I fell for her at once, charmed by her Irish eyes, galactic smile, and dulcet ways. But she was taken, by a lucky fellow I’d just hired, Eric Newton. So, I settled for friendship, and we three formed a youthful bond that endured as we aged.

Mary Ann died in 2019, claimed by rampaging cells. Dying is an untidy process that always leaves something – or much – undone. When the lymphoma took Mary Ann, she hadn’t yet finished the book that was to be the culmination of her life’s work, a memoir about losing and finding herself, about leaving and returning home, and about her father, the former literary editor of the San Francisco Chronicle. The book lacked a final chapter, which Mary Ann had planned to write after returning home from the East Coast to Mill Valley, California.

Before she died, Mary Ann asked Eric to keep her book alive, to make it whole and write the last chapter. In their decades as a couple, she the writer and he the editor, they regularly wove words together. Each nourished the other. So it was a natural thing to do.

***

In the book, Eric describes one of their final conversations:

The last time we went over the manuscript, after we finished, she just looked at me. It was not the please-grab-a-towel look but the deep-blue-sky look.

And she said . . . nothing.

Not a word. No need.

She was dying. We both knew what she was asking. I hugged her pages to my chest.

“You know I’ll do it.”

***

And he did.

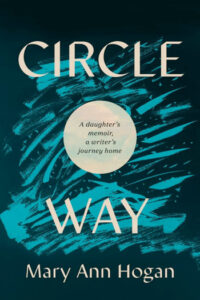

The result is Circle Way, a lyrical, deeply personal, honest, and often whimsical collage of Mary Ann’s artful story-telling and her father’s poetic ruminations and ephemeral drawings. It is a three-dimensional memoir that presents the life of a writer shaped as much by what she overcame and what she accomplished as by what her father, despite his professional success, failed to do, which was to write his own book.

“In so many ways,” Mary Ann writes, “I am my father’s daughter. Self-made journalists, we. Introverts, lovers of books and wine. Sufferers of ‘flying thoughts.’ We once held prized newspaper jobs, writing for the masses. But we felt like impostors with nothing to say. At times I still do.”

Flying thoughts, swirls of emotions, the curve of life, the inward spiral, the outward gleam of the nautilus shell. This is the path Mary Ann followed, avoiding the straight lines, accepting the looseness of history and ignoring the conventions of time. She didn’t want to just tell a story; she wanted to tell a whole story, using what was available, what could be grasped, what could be disinterred, and what could be intuited from what she had seen and lived.

We all live with doubt about the rightfulness of the choices we make. Knowing what to do is often more vexing than the doing. Author Katie Kitamura, in her enigmatic novel, A Separation, writes a piercing line that is apt here: “People were capable of living their lives in a state of permanent disappointment.” What Mary Ann allows us to see in Circle Way is a daughter’s recognition of her father’s discontent and how, using that perception as a beacon, she found a way to elude his legacy.

Acknowledging the prejudice of my friendship, as well as my reading of several versions of the manuscript, I can say Circle Way is a remarkable book. Or to say it in a manner that Mary Ann would approve, I saw the sausage being made and still found it delicious.

One final word: What Mary Ann did, and what Eric helped her do, was not just write a memoir, but create something uniquely personal. Anyone who attempts creative expression knows how difficult that is to do.

Mary Ann, the journalist, did not want to get scooped on the news of her death, so she wrote her own obituary, one about Mary Ann the writer. Here’s an excerpt:

“Mary Ann saw death not as an ending, but rather as the beginning of the final, infinite chamber in the nautilus shell of a creative life. . . .”

***

How to buy Circle Way: