The book from the last Oaxaca workshop arrived the other say. The cardboard package was on the stairway landing inside the front gate when I arrived home from an afternoon shoot. I took the book inside to the kitchen, slit the packing tape with a paring knife and opened the wrapping.

The book from the last Oaxaca workshop arrived the other say. The cardboard package was on the stairway landing inside the front gate when I arrived home from an afternoon shoot. I took the book inside to the kitchen, slit the packing tape with a paring knife and opened the wrapping.

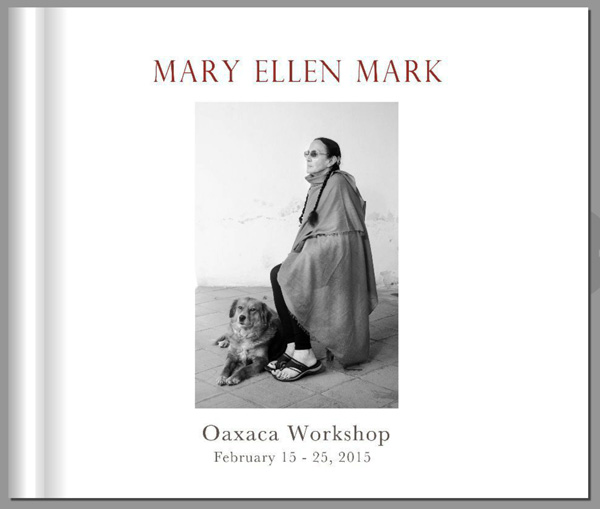

There was Mary Ellen on the cover.

In the photograph she is seated, facing to her right. A dog lies at her feet, his head raised and cocked slightly, his eyes looking into the camera. A large shawl covers most of Mary Ellen’s body. Only her head, her braids, a bit of her legs and her feet are visible. A large lump appears beneath the shawl on the left of her body. It is the cast on her broken wrist. She wears sandals. Her toenails are painted black. Her feet appear to be large for such a tiny person.

It is a somber image. I would have said that even had she not died just three months after the picture was made. She isn’t smiling, but she rarely did for photographs, so it isn’t that. It’s the tightness of her face, the downward slant of the corners of her mouth, the hunch of her shoulders below the shawl. They create an uncharacteristic appearance of smallness for a woman whose personality was as large as the life she led.

In the photograph I see the sickness. I see the frailty. I see weight she carried, the knowledge that her time was running out and that despite all her fierce will and immense soul – the characteristics that defined her – she could not prevent it from doing so.

I touched the picture with my right hand and cried.

***

The truth is I didn’t buy the book until after Mary Ellen died. The February workshop in Oaxaca didn’t end well for me – nor for Mary Ellen – and when the workshop organizers sent word that book was finished I hadn’t cleansed enough of the bad feelings to want to buy it.

The workshop wrapped up on Wednesday night and most everyone flew home the next day. Mary Ellen was there an extra day and I was staying through the weekend to do more photography. I planned to ride to the airport with her on Friday morning to help her navigate the craziness in the terminal should she need it.

The workshop wrapped up on Wednesday night and most everyone flew home the next day. Mary Ellen was there an extra day and I was staying through the weekend to do more photography. I planned to ride to the airport with her on Friday morning to help her navigate the craziness in the terminal should she need it.

On Thursday morning, I went to an elementary school outside of Oaxaca to photograph a teacher, a young Mexican woman who had returned home to Oaxaca after living illegally through her adolescence in South Carolina, a placed she considered so racist and intolerant that she chose to return to Mexico. After cabbing back into town, I was walking through the zócalo in the mid-afternoon en route to my apartment when I spotted Mary Ellen seated on the patio of her hotel. Before her on a table were many of the contents of the two shopping bags she carried with her – papers, folders, receipts, etc. She was quite upset.

“I was robbed,” she told me after I sat down next to her. She explained that 30 minutes earlier while shopping she accidentally left a wallet containing a sizable amount of Mexican pesos on the counter of a store. After leaving the store and discovering that the wallet was missing, Mary Ellen sent her assistant back to retrieve the wallet. It was gone.

Mary Ellen was enraged. She wanted to call the police. I won’t come back here, she said. I’ve had it with Mexico. The people can’t be trusted. The city has changed so much. It’s not the same.

They were harsh words and they saddened me. I knew she was sick. I knew her health might not allow her to return for the workshop she’d already planned for later in the year. If this trip were to be the last of her two-decade love affair with Oaxaca, I didn’t want it to end so bitterly.

I went to the store. Mary Ellen’s assistant was there, arguing with the clerk and the owner, who, coincidentally, I had known for a couple of years. The assistant, a young Mexican guy, was sure the clerk had taken the money (I know my people, he told me later, outside the store.) I wasn’t yet convinced. Mary Ellen always seemed to be looking for things – a folder, a pair of glasses, something. It seemed reasonable that she might have misplaced the wallet elsewhere.

The shop owner let us look behind the counter, in shelves and drawers and all around the store. Nothing. I returned to Mary Ellen’s hotel. She hadn’t calmed down and continued to talk about getting the police involved. Don’t, I told her. Don’t. This is Mexico. It won’t go well. She ate dinner that night with a friend and I didn’t see her again until 6:30 the next morning, when we met in the lobby of her hotel.

A night’s sleep hadn’t helped. “She stole it. I know,” said Mary Ellen right off. After a night of thinking about it, I still wasn’t sure even though the amount of cash in the wallet equaled a month’s pay or more for a shop clerk. It would be hard to resist. We’ll never know, I told her; you’ve got to let it go.

The driver arrived, someone Mary Ellen had used for years. Two days earlier I’d heard him and Mary Ellen agree on a price to take the two of us to the airport and then give me a ride back into town. Now he wanted to charge us double because of the return trip. It was a standard tactic in Mexico, but it further upset Mary Ellen. No, she said. No. Her mood worsened. There’s no loyalty here, she said, no loyalty.

At the airport, all went smoothly. Mary Ellen and I hugged goodbye. After I watched Mary Ellen clear security, I got in the car for the 20-minute return trip into the city. I never saw her again.

***

A couple of days later I flew home to San Francisco in my own negative mood. I was disappointed in my work. I didn’t like the pictures I’d made. I was exhausted from the heat and had lost five pounds from walking miles every day and I couldn’t see the value of it in the photographs. They were too ordinary, too magazine-y as Mary Ellen would say. I felt like I would never make a good picture.

This state of mind is important in order to understand what happened next. After each workshop with Mary Ellen, there is a flurry of Internet activity among its participants, especially on Facebook. Groups are formed, photos are shared and quips are exchanged. Less than a week after I returned to California, one of the photographers from the workshop posted some photos that deeply disturbed me. I won’t say what the subject was, where they were shot or who made them, but I thought they were a violation of privacy and a breach of trust.

I can be overly opinionated and judgmental – not my finer characteristics – and the pictures outraged me. They hit the sweet spot of disdain I have for privileged First World travelers who come to Mexico and treat the poor people they encounter with (what I see as) disrespect. Anyone who knows me has heard the rant: They can’t speak the language, they enter people’s homes without so much as a please and thank you, they show up at sacred ceremonies and snap away like they’re photographing a Little League parade.

I’ve done it, too. I plead guilty. But I do it less and less. I am working on patience and intimacy. I am OK with spending the whole day with someone and not taking a single picture. I would rather – even if my success rate is low – be a better human being than a great (or even a mediocre) photographer. Thank you, Mary Ellen, for teaching me these things.

In short, I was angry when I saw the photographs. I wrote an email to the photographer. I tried to be polite and persuasive, but I probably sounded condemning and abrasive (see above). The photographer disagreed with me. The photos stayed online.

It seemed so wrong to me that it made me question my own photographs. Am I exploiting people? Am I betraying their trust? I still don’t know the answers to those questions, but what I did know was that I was done with workshops. No more, I told my wife, a former journalist who had lived and worked in Mexico. No more photography – or Oaxaca – with others. I would continue my relationship with Mary Ellen, travel to New York to visit her, nourish the friendships I’ve made through her and work in Oaxaca on my own. But no more groups, not with anyone.

This was my mindset when the workshop book came out. I looked at it online, flipped through the digital pages and saw only the negative.

I didn’t see the faces of my friends, I didn’t see the effort and creativity of the other photographers, I didn’t see the dinners with Mary Ellen and her posse of fabulous women, I didn’t see the hopes and hardships of the families I’d visited, I didn’t see the drunken, almost desperate frivolity of the transvestites I’d come to know, I didn’t even see the sweetness of the abandoned children I’d photographed for two years. I only saw what I’d failed to do. I only saw how others had disappointed me and how I had disappointed myself. I didn’t buy the book. I didn’t want those memories.

When Mary Ellen died, I, like every other photographer she had ever helped, was heartbroken. I wanted more of her. I spent hours online looking at her work. Eventually, I looked through the workshop book again. This time it was different. I only saw her.

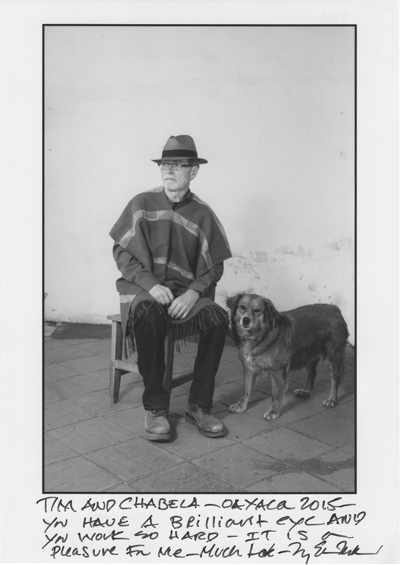

There she was surrounded by her assistants – steady Cristina, mercurial Beto, thoughtful Ina, energetic Candy, and earnest Paula. There she was in her photographs of the participants, some of whom I feel closer to than friends I’ve had for years. There she was in her photograph of me, I looking small, old and awkward. The dog looked better.

There she was in the work of the photographers – the girl in the locker by Alejandra; the oily men against the wall by Bjorn; the gauzy Holga dog by Chae; the beautiful image of the young orphaned boy in a box by Grant (who worked so hard); the boy in the shelter hanging upside down off a concrete wall by Ina; the dog at the dump by James; the hands of a mother cupping her disabled son’s head by Jody (who has been photographing this child for years); the drummer boy by Lori; and the girl in her communion dress against a blue wall by Julia. And so many others.

Now, I see everything I didn’t see in the book the first time. I see goodness and humanity and passion. I see innocence and experience. I see admiration and awe (by the photographers of Mary Ellen) and I see loyalty and relentless encouragement (by her to them). And, I see myself, still uncertain at this age, still wanting to be more, still dissatisfied, but still trying.

I think that’s what she saw in me. I certainly see that in her.

OAXACA, Mexico – The late documentary photographer

OAXACA, Mexico – The late documentary photographer