February 28, 2003

Bemoaning the Owning

The FCC held its first - and only - public hearing yesterday on proposed changes to its media ownership rules that, if adopted, could result in further consolidation in the entertainment and news industries.

While most of the FCC rules regulate broadcast companies [see this guide to media ownership rules under review] newspapers are affected because the FCC restricts media companies from owning a newspaper and a TV station in the same market (some cross-ownership was grandfathered in when the ban took effect in 1975).

For example, when the Hearst Corporation bought the San Francisco Chronicle in 1999, FCC restrictions prevented it from buying KRON-TV, the then-NBC affiliate in San Francisco, which was also for sale by the Chronicle company. KRON was later sold to Young Broadcasting of New York and lost its network affiliation.

As I've said here several times [read Competition and Mediocrity or Is Big Media Really Bad News?], I'm not convinced that consolidation of ownership will result in a reduction of journalistic quality. Certainly, to use the inverse in support of my negative, the proliferation of cable news and entertainment programming hasn't resulted in an increase of quality. (Can broadcast news get worse than it is? Can newspapers become more inert?)

Whenever possible, I favor competition, which I think breeds innovation, something newspapers desperately need these days. But, the information technology revolution of the last two decades has altered the nature of media competition. The playing ground is more level, granting newer, technology-enabled voices access to wide audiences.

The news media race of the future belongs to the quick and the nimble. The irony is that should the FCC loosen ownership restrictions, Big Media may discover that being bigger, and therefore more cumbersome (let's all say AOL Time Warner), is not necessarily better for business in a world that values change more than constancy.

Here is a sampling of reporting from and commentary on the FCC hearing:

![]() Washington Post: "Still, much of the debate over media ownership revolves around goals that sound laudable but are short on specifics.

Is it competition when eight of Washington's major radio stations are owned by Clear Channel?"

Washington Post: "Still, much of the debate over media ownership revolves around goals that sound laudable but are short on specifics.

Is it competition when eight of Washington's major radio stations are owned by Clear Channel?"

![]() Los Angeles Times: "Powell (FCC Chairman Michael) warned the audience against turning to the government to determine what should be aired. He noted that often the TV shows attacked as low-quality earn the highest ratings. 'Half of what we're railing about is what people choose' to watch, Powell said."

Los Angeles Times: "Powell (FCC Chairman Michael) warned the audience against turning to the government to determine what should be aired. He noted that often the TV shows attacked as low-quality earn the highest ratings. 'Half of what we're railing about is what people choose' to watch, Powell said."

![]() Ad Age: "Media consolidation is producing 'raw sewage' TV content, a consumer spokesman charged.

A network executive, however, said that curbs on consolidation were what was really hurting TV content."

Ad Age: "Media consolidation is producing 'raw sewage' TV content, a consumer spokesman charged.

A network executive, however, said that curbs on consolidation were what was really hurting TV content."

Thanks for the links to Journalism.org, which through the Project for Excellence in Journalism maintains an extensive, although generally anti-consolidation, list of resources on the issue.

February 27, 2003

Mini Me(dia)

I'm getting whiplash from following the polemic about whether blogging is journalism.

The troglodyte traditional journalists (thanks to J.D. Lasica for the caveman reference) hunker defensively in their newsholes, refusing to acknowledge how changing media is affecting their profession. The nouveau J-bloggers strut their stuff publicly, offering opinion, insight and sometimes invective, often without acknowledging that the news to which they are reacting was provided by the traditional journalists.

What we have here is the men-women-Mars-Venus thing: Most bloggers are not (or haven't been) journalists, and most journalists are not (but maybe will be someday) bloggers. For now, they just don't get each other.

This is a dysfunctional dynamic that fails to embrace the flattening of the information hierarchy brought about by the advances of nano-publishing software and miniaturization of image-capture technology.

Glenn Reynolds, the Instapundit, writes in his column for Tech Central Station that "the coming thing in alternative web media is multimedia," digital photos and videos made to record an event (a basic component of journalism) or to propagate a point of view.

Reynolds points to a video made by conservative commentator Evan Coyne Maloney about the anti-war protests in New York and says: "Equipped with a camera and a microphone, and fairly rudimentary titles and editing, Maloney produced a video that reached literally millions, and that sent a message very, very different from the one that mainstream media were sending about the protests and those protesting."

This type of what Reynolds calls guerilla media, and what I call mini media, supports the argument made by blogging guru Dave Winer in an interview with News.com that mainstream media, in its deteriorated, lowest-common-denominator state, adds little value to the news. Winer says:

"The typical news article consists of quotes from interviews and a little bit of connective stuff and some facts, or whatever. Mostly it's quotes from people. If I can get the quotes with no middleman in between--what exactly did CNN add to all the pictures?"

Responding to Reynolds, Jeff Jarvis of BuzzMachine keys on one of my favorite points: "The cost of media production is falling to near-zero at the same time that the retail value of content is falling rapidly."

The value of public information is approaching nil. Newspapers (and news networks), which once perched haughtily atop the information pyramid dispensing a well-measured dose of daily news, now share space on an always-on, ever-expanding mini-media continuum whose agenda is rapidly slipping from their control.

The question asked by Winer (what exactly did CNN add to all the pictures?) has to be answered as well by newspapers (what exactly did we add to the information?). Or, to put it another way: What type of journalists are we going to be?

The future of newspapers depends on how they define themselves in the world of journalism regardless of how many others choose to enter it.

Links

![]() News.com Blogging comes to Harvard

News.com Blogging comes to Harvard

![]() Glenn Reynolds Guerrilla Media

Glenn Reynolds Guerrilla Media

February 26, 2003

Competition and Mediocrity

I've been on the road, I'm over deadline on a story and now I'm fighting a flu I'm sure I picked up while planebound for two hours on a DFW tarmac during an ice storm. That's why I missed Janet Kolodzy's rant in the Christian Science Monitor yesterday about the emptiness of the argument that competition in the news media results in higher quality journalism.

"Conservatives argue that competition allows the best to thrive. Liberals argue competition brings diversity. But the sorry state of news today proves they're both delusional. It's time to admit to the public what most people in the trenches of the news business already know: competition doesn't bring quality and diversity. Competition brings profits to shareholders and overhyped, underreported, mediocre journalism to the public."

Kolodzy, who teaches journalism at Emerson College in Boston, argues that the current brouhaha over the FCC's pending reconsideration of media ownership regulations is a smokescreen that obscures the real issue: "Competition has led to copycat, lowest-common-denominator news."

Agreed. But even worse, most news organizations, and newspapers in particular because they generally operate in a monopoly environment, don't even understand what they should be competing against.

Hours of airtime and yards of newsprint are devoted to competitive coverage of the Big Story of the day - an unfortunate transplant, a missing woman, a president hell-bent on war - and the result is incremental additions of factoids that blend together to form an information generica. A newspaper must compete for mindshare by being different - not the same. Only then can it separate itself from the news noise and provide a unique voice for its community.

When Foreign Policy published a similar article last month, I asked: Does concentrated ownership also reduce the quality of journalism? [ Read "Is Big Media Really Bad News?" ]

Kolodzy puts the question another way: "The issue is not who owns the media; it is what they do with it."

UPDATE, Feb. 27: The AP reports that "rules that limit ownership of newspapers and radio and television stations are just months away from a broad overhaul that could pave the way for more media mergers and alter the landscape of news and entertainment programming."

Links

![]() Christian Science Monitor Regulating the news

Christian Science Monitor Regulating the news

"We Are Not Monks"

The above quote came from Orville Schell, dean of UC-Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism when I interviewed him for a story that appears in this month's issue of the American Journalism Review. He was referring to the Starbuck's-level salaries small newspapers pay to reporters and editors. "You can only abuse people so much," said Schell. "They have families, children and student loans and lives to lead. We are not monks."

The story reports on the ongoing challenge small-town editors face to fill seats in their newsrooms, and the growing reluctance of journalism-school graduates to take those jobs.

I told the story mostly through the experiences of one small Northern California newspaper, the Vacaville Reporter, whose editor, Diane Barney, struggles daily to produce quality journalism. "We have periods where we're a better newspaper and periods where we're not so good because of the learning curve that we have with the staff as it changes and fluxes," says Barney. "We can't really ever say we're there, or we've attained it, or we're done. It's not like the 'we' stays the same. The 'we' is constantly changing."

Links

![]() American Journalism Review Vacancies in Vacaville -- Young journalists are increasingly reluctant to work long hours for low pay in less-than-glamorous locales. The result: high turnover and empty desks.

American Journalism Review Vacancies in Vacaville -- Young journalists are increasingly reluctant to work long hours for low pay in less-than-glamorous locales. The result: high turnover and empty desks.

February 21, 2003

Cutting Through the Crowd-Size Cloud

I am traveling today and didn't intend to post, but felt compelled to put up a quick pointer to the excellent examination by the San Francisco Chronicle of the crowd size at last weekend's anti-war protest. [Read The Numbers Game].

The Chronicle hired an aerial survey company to take high-resolution photographs of the protest as its peak and concluded the march and rally against war in Iraq drew about 65,000 people instead of the 200,000 estimated by police and organizers.

At a time when emotions are running hot on all sides of the political spectrum - with conservatives in particular attacking the press for being too soft on protest organizers --

the Chronicle did exactly what a good newspaper should do: Take whatever steps are necessary to get at the truth.

[Thanks to MediaMinded for the pointer to OpinionJournal].

Links

![]() San Francisco Chronicle Photos show 65,000 at peak of S.F. rally

San Francisco Chronicle Photos show 65,000 at peak of S.F. rally

![]() San Francisco Chronicle Using aerial photography to estimate the size of Sunday's peace march in S.F.

San Francisco Chronicle Using aerial photography to estimate the size of Sunday's peace march in S.F.

February 20, 2003

Write it Again, Sam

Given the name of these humble scribblings, I can't pass up the opportunity to point to Chip Scanlan's latest column, in which he argues that "just because journalism is 'the first rough draft of history' that shouldn't give writers -- and their editors -- an excuse to publish their first drafts every time."

Scanlan, who teaches newswriting at the Poynter Institute, points out correctly that most "newswriting is the product of a first draft culture" that values speed and brevity over revision and depth.

"The most compelling argument for revision," says Scanlan, is illustrated by "a piece of advice that the editor of the Wall Street Journal gave to a new editor toiling away one night on a story."

"Remember," Barney Kilgore told Michael Gartner, "the easiest thing for the reader to do is to quit reading."

Good writing alone will not save newspapers, but it might keep a few more eyeballs on the pages.

Bob Baker, a Los Angeles Times reporter who publishes Newsthinking, an online newsletter about journalistic nuts and bolts, is chronicling his return to reporting after years of editing.

Baker's openness about his difficulty during the transition, which he labels his rehab, of resurrecting dormant writing skills illuminates the thoughtfulness and care a good writer puts into his work. [Read it here.]

February 19, 2003

Shutting Down the News Factory

Dressed in his trademark bow tie, striped shirt and tweedy jacket, Philip Meyer wears the image of college professor well, not offering a sartorial clue that beneath the academician's exterior beats the heart of a man on a mission.

Dressed in his trademark bow tie, striped shirt and tweedy jacket, Philip Meyer wears the image of college professor well, not offering a sartorial clue that beneath the academician's exterior beats the heart of a man on a mission.

Meyer is alarmed. And if you're in the newspaper business he wants you to be alarmed, too.

Speaking to a recent Poynter Institute conference on Journalism and Business Values, Meyer preached his gospel of "quality equals credibility equals profits" and reminded the gathering that daily newspaper readership has been declining about 1 percent annually since the 1960s. "By my calculations," Meyer said, "the last daily reader will disappear in September 2043."

So far, though, Meyer, who directs The Quality Project at the University of North Carolina, has been unable to create a metric linking quality and profit that could wean Wall Street and industry executives off their quarterly suckling of the bottom line. And, as Poynter reporter Robin Sloan points out, without a "causal link between quality or influence and business performance quality will continue to be a tough sell." [See Does Quality Matter?]

The problem is one of perspective. The prevailing discussion in the business right now is about how to make money in spite of putting out a newspaper. A proposal for a new journalism business model put forth last year by New Directions for News suggested: "The real alternative to the current situation is not a business that values profits AND good journalism, but a business where good journalism IS the business."

This proposal, crafted by Dan Sullivan, a media economist at the University of Minnesota, suggests that a journalism-based business must be a "service-based business, not a manufacturing one" that "must measure impact, not just products sold, but benefits provided."

Sullivan's characterization of the current manufacturing mindset both in newspaper boardrooms and newsrooms is key to understanding the barriers to change in the industry.

On the business side, publishers have huge investments in printing, information and distribution technology designed to do one thing - lower per unit (i.e., per newspaper) production cost. Changes in this system would be disruptive and expensive.

On the content side, the technology transfer of the last two decades that brought the backshop into the newsroom created an assembly-line environment on news and production desks that emphasizes speed over quality, and the development of secondary news products such as zoned editions means these news-hole beasts must be fed, resulting in demand for breadth (quantity) over depth (quality).

To produce newspapers in this manner requires efficient, repetitive action - papers are scripted in advance, before the news happens; reporters are told how long to write, before they cover the stories; photographers are given dimensions of an illustration, before they take the pictures. This way of working discourages innovation and encourages rote behavior. At a time when journalists are better educated than ever before, it is ironic how many of them still work on the factory floor.

Links

![]() The Quality Project

The Quality Project

![]() New Directions for News

New Directions for News

![]() Dan Sullivan Business Models for News

Dan Sullivan Business Models for News

February 18, 2003

Covering War in a Free Society

This week news organizations will give to the Pentagon the names of the 500 reporters, photographers and cameramen who intend to cover the U.S. invasion of Iraq.

This is a historic - and welcome - reversal of the government's exclusionary policy toward news coverage of U.S. military action. As the New York Times reported today, "For the first time since World War II and on a scale never before seen in the American military, journalists covering any United States attack on Iraq will have assigned slots with combat and support units and accompany them throughout the conflict."

Access to war means proximity to danger. The Pentagon has been running boot camps for would-be war correspondents [ Read John Koopman's first-hand account ], who, unlike their counterparts in World War II, will not carry weapons (although they must provide their own helmets and flak jackets.

War is, by nature, deadly, and, by extension, so is reporting on one. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, eight journalists were killed covering the short war in Afghanistan and 60 died in the last decade in various cross-fires around the globe, most of them photographers or cameramen.

Harold Evans, in a compelling essay written for the Newseum on the history of war reporting and the nature of the people drawn to it, asks, "Is journalism worth dying for? Is history worth dying for?"

Indeed, Evans is asking, is truth worth dying for?

That is a question each correspondent must ask himself or herself. Most will answer yes, and some of them, despite all precautions, will die in this coming war.

Others will witness acts of inhumanity that will haunt their remaining days. Evans tells the story of Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Kevin Carter who "convinced himself that he was right in the mid-1980s to photograph the first known public execution in South Africa by 'necklacing,' setting fire to a gasoline-filled tire around someone's neck. 'I was appalled at what they were doing. I was appalled at what I was doing. But then people started talking about those pictures... then I felt that maybe my actions hadn't been at all bad. Being a witness to something this horrible wasn't necessarily such a bad thing to do.' Carter later took his own life."

And for some of these reporters and photographers who cover the Iraq War, the horrors and heroics they witness will make them better journalists.

David Halberstam, in an interview that is part of the Newseum exhibit on war correspondence, says, "I always thought my life was more precious coming back. I, I thought I always worked harder on stories when I came back from Vietnam. I, I never took being a reporter, a reporter in a free society, I never it took it for granted again. I'm 66 now and I still work as hard as I did when I was young. And I, I think part of that is Vietnam, the, the good fortune to go there, to, to do well, to be lucky enough to live when others who were just as good as you were and weren't quite as lucky died. I think the sense that your life is a privilege and that you were the beneficiary of something and therefore you owe it, I think that has always stayed with me and so I've always continued to work hard. And I think it's because I think my life is a gift and some of that is due to Vietnam."

Increasingly, as modern conflicts become less decisive and more chronic, little good seems to come of war (if indeed much ever did). As journalists, though, we can hope the current generation of war correspondents is as fortunate as Halberstam was - that they not only survive but are also compelled to excel as "reporter(s) in a free society."

Links

![]() Harold Evans Reporting in the Time of Conflict

Harold Evans Reporting in the Time of Conflict

![]() Newseum War Stories

Newseum War Stories

![]() Committee to Protect Journalists

Committee to Protect Journalists

![]() Editor & Publisher U.S. Military Document Outlines War Coverage

Editor & Publisher U.S. Military Document Outlines War Coverage

February 14, 2003

Grazing the Blog Buffet

A lot gets said about journalism in the Blogosphere. Here are some recent topics I haven't written about:

![]() Media Bias -- Slate media columnist Jack Shafer kicked up a dust storm with two columns [ Part 1; Part 2 ] on bias in the news media. The first began: "Political bias - raw and wicked - blights American newspapers and TV news. Upon this bold declaration, press critics of both the left and right are able to agree."

Media Bias -- Slate media columnist Jack Shafer kicked up a dust storm with two columns [ Part 1; Part 2 ] on bias in the news media. The first began: "Political bias - raw and wicked - blights American newspapers and TV news. Upon this bold declaration, press critics of both the left and right are able to agree."

Read commentary from Rhetorica's Alan Cline (who often writes about the inherent nature of bias), MediaMinded and Bill Dennis.

Also, Eric Alterman of MSNBC and Brent Bozell of the Media Research Center debate the question: Are the Media Liberal?

![]() Nano Publishing - SiliconValley.com's Dan Gillmor sees micro-content as "an emerging brand of Internet-based journalism that is helping shape the future of news." He cites Gizmodo and Gawker (both Nick Denton creations) as narrow-focused blogzines with a chance for commercial success.

Nano Publishing - SiliconValley.com's Dan Gillmor sees micro-content as "an emerging brand of Internet-based journalism that is helping shape the future of news." He cites Gizmodo and Gawker (both Nick Denton creations) as narrow-focused blogzines with a chance for commercial success.

![]() Journalism Education - Village Voice reporter Nat Hentoff caused a ruckus by deciding to use the controversial book "Coloring the News: How Crusading for Diversity has Corrupted American Journalism" in a graduate course he teaches at NYU. The National Association of Black Journalists objected.

Journalism Education - Village Voice reporter Nat Hentoff caused a ruckus by deciding to use the controversial book "Coloring the News: How Crusading for Diversity has Corrupted American Journalism" in a graduate course he teaches at NYU. The National Association of Black Journalists objected.

Read commentary from Rhetorica ("This is an example of the exceedingly silly notion that a professor's choice of books equals promotion of said book's ideas.").

![]() Investigative Reporting - IRE launched a blog this week that highlights good investigative work. It's put together with the help of Derek Willis of thescoop.org.

Investigative Reporting - IRE launched a blog this week that highlights good investigative work. It's put together with the help of Derek Willis of thescoop.org.

February 13, 2003

The Morning Snooze Wakes Up

A lengthy story in the weekly Dallas Observer about changes underway at the Dallas Morning News touches on two critical issues for newspapers - leadership and the definition of news.

Setting aside an historically antagonistic relationship with the Observer, which for years published a snarky column called Belo Watch, the Morning News opened its doors to writer Eric Celeste, granting him extensive access to Editor Bob Mong and Publisher James Moroney. Once inside, Celeste found managers who acknowledge the newspaper's weaknesses and are trying to correct them, but have yet to convince a skeptical newsroom that change is for the better.

The piece opens with Mong speaking to a gathering of his staff and urging them to aspire to "passionate virtuosity," but, according to Celeste, his intended inspiration fell not only on deaf ears but faint hearts.

"The speech was heartfelt. Mong had wrestled with it for weeks, certain that his oration would fill reporters with hope, make them ready to tackle the city with investigative zeal. He included in it a simple, telling anecdote that illustrates the difficult path the DMN faces, likening the paper's journalistic progress over the past 20 years to a sprinter who's shaved his 100-yard dash time from 11 seconds to 10 flat. But, he said, to be world-class, we've got to go from 10 to 9.75 seconds--not nearly as far, but twice as hard to achieve.

"When he finished, Mong took a drink of water. 'Any questions?' he asked the throng. Not one reporter dared to question, praise or challenge."

Incredible. Even accepting the rationalization that years of management abuse had cowed the Morning News reporters into a state of permanent timidity, the muted response demonstrates what L.A. Times media critic Dave Shaw calls the "void in our profession" of powerful newsroom characters, an absence engendered by the "rise of respectability and the decline of raffishness." It is impossible to imagine someone like Bella Stumbo sitting silently on her hands after her editor had challenged her to be a better reporter and then asked, "Any questions?"

My point is this: Newspaper managers are not only in a position where, in order to survive, they must innovate and inspire - a tough enough task in a business where success has come through repetition and hierarchy - but they also must sell those changes and hopes to newsrooms where inertia and defensiveness [read Passive/Defensive Personality] are common traits.

Other sections of the Observer's story highlight the deepness of this gap between the actions of leadership and the reactions of rank and file.

For example, Morning News Publisher Moroney refreshingly links circulation and profit to the quality of content:

"When the circulation starts to stagnate, when it starts to go in the other direction, we've got to look up and say to ourselves, 'Is there something about the product that is causing this to happen?' Because Bob and I firmly believe that it starts with content. If you improve the content, then circulation starts to grow. Then I can price my advertising on that circulation growth, then I make more revenue. If I make more revenue, normally I have more profitability. If I'm more profitable, I get investment capital back to invest in the product to make its content even better. And the whole cycle starts again. It all starts with content."

To reinforce this connection, Moroney ups his own eccentricity quotient a bit by handing out a $100 bill to any staff member who can recite the paper's five business objectives: Increased revenue; Increased circulation; Publish a daily Spanish-language newspaper in two years; Put out two new products (e.g., a weekly tabloid aimed at younger readers) that will be distributed within the paper; The Collin County initiative.

It is this last goal - to increase readership in the rapidly-growing, affluent suburbs north of downtown Dallas - that seems to rankle reporters most.

" 'I don't care what they say, people are freaked out about it career-wise,' says a reporter. 'Sending an experienced reporter to Plano, it's like taking the quarterback and making him the holder. Yeah, it's important to the team, but you're still the freaking holder. It will take a generation of change before people will not see Plano as a demotion.' "

It's sad that this unnamed reporter's words so accurately reflect an endemic newsroom sentiment. Many, if not most, reporters see suburban coverage as an anathema. How wrong they are. Good storytellers tend to find good stories wherever they go. [Read this feature story from Yakima, Wash.]

Take New York Times reporter Charlie LeDuff as an example. After playing a pivotal role in the Times' Pulitzer-prizewinning series on race in America, the paper sent LeDuff to Los Angeles, where his colorful writing about "ordinary" things such as rain [third item] and a rat problem in Beverly Hills brought him scorn from the local media.

That reporter's whine about Plano made me think of a scene from the movie "Adaptation" in which a screenwriter, horribly blocked and unable to finish his script, complains to a voluble writing coach about the lack of drama in the "real world."

The writing guru responds with this rant:

"The real world? The real fucking world? Are you out of your fucking mind? People are murdered every day! There's genocide and war and corruption! Every fucking day somewhere in the world somebody sacrifices his life to life to save someone else! Every fucking day someone somewhere makes a conscious decision to destroy someone else! People find love! People lose it, for Christ's sake! A child watches her mother beaten to death on the steps of a church! Someone goes hungry! Somebody else portrays his best friend for a woman! If you can't find that stuff in life, then you, my friend, don't know much about life!"

Take out screenwriter. Substitute reporter. Delete "real world." Insert Plano. Start writing.

Links

![]() Dallas Observer Snooze Alarm -- What will The Dallas Morning News look like when you wake up in 2010? If Editor Bob Mong has his way, it'll be the best damn paper the 'burbs will buy.

Dallas Observer Snooze Alarm -- What will The Dallas Morning News look like when you wake up in 2010? If Editor Bob Mong has his way, it'll be the best damn paper the 'burbs will buy.

February 12, 2003

Vox Electronica

APME (Associated Press Managing Editors) is sponsoring a tactic designed to get more voices of ordinary people (as opposed to extraordinary public figures) into stories - email interviews.

Kent Warneke, editor of the Norfolk (Va.) Daily News told Editor & Publisher his paper sought email reaction from readers for a state budget story and received 58 responses. "It's a great way to get different names and people in the paper," said Warneke. "It takes time away from having to call and interview that many people."

Is this a good idea? Sure, email is efficient, but reducing even further the direct communication between reporters and sources doesn't seem like a step forward. It's bad enough that public officials and corporate officers increasingly ask for written questions from reporters so they can answer in formulated and vetted language. Now it seems that readers are being morphed into a pack of mini-pundits.

Consider these email responses the San Francisco Chronicle received recently when it asked readers: Will the change from yellow alert to orange affect your plans?

"The idea of soft targets is, I am convinced, irrelevant outside of large cities. .... Frankly, the high alert, combined with a lack of particularity, strikes me more as federal fear-mongering than a significant warning."

And:

"As a basic philosophy I ignore any terrorist threat so vague and nonspecific as to be useless in daily life. Living in fear hands victory to vermin who are too cowardly to show their faces."

Or, when the Chronicle sought reaction to President Bush's State of the Union speech:

"He did not change my mind. I know the implications of letting Iraq off the hook. I know the implications of war. I don't like either of them. I am really caught between "Iraq and a hard place."

Iraq and a hard place? These read like (poorly written) letters to the editor, not spontaneous responses. Admittedly, "reaction" stories typically have little value. They are a random selection of quotes gathered from whomever a reporter could convince to answer a question before deadline, but at least they contain real voices and that is a basic goal of reporting - authenticity.

Anything that falsifies those voices and encourages already desk-bound reporters to spend more time in the newsroom rather than outside of it doesn't seem like a good idea to me.

Links

![]() Editor & Publisher E-mail Delivers Sources for Newspapers

Editor & Publisher E-mail Delivers Sources for Newspapers

February 11, 2003

There's Nothing Left but the Journalism

Here's a statement in the Columbia Journalism Review that has an alarm quotient equal to an orange alert from the Department of Homeland Security: "At stake is nothing less than the future of print journalism."

Newspapers companies, having watched classified advertisers take more and more of their trade to less expensive and more effective Web companies such as Monster.com and Autotrader.com, are now seeing their deepest readership fear come true - would-be print subscribers gobbling up newspaper content for free on the Internet.

Although a study last summer by Belden Associates concluded that online readership does not cannibalize print sales, Greg Harmon of Belden did tell Editor & Publisher that growing web readership might eventually "negatively affect single-copy print sales."

Whatever short-term comfort publishers took from those findings gave way to further unease when comScore reported that the audience for newspaper sites is growing far more rapidly than Internet use as a whole. And yet another study, this by Forrester Research, found that "consumers with six years of Web experience are three times more likely than Internet newcomers to decrease their print newspaper reading," according to CJR, which quotes a comScore executive saying, "Newspaper circulation has been declining for years, and you see an online segment with great increases. One plus one equals two."

It all adds up to a rush by publishers away from free Internet content and toward online subscriptions - and toward continued denial of the underlying problem, which is that too many potential print subscribers simply don't view the product as worth paying for.

The ever cogent MediaSavvy [thanks for the pointers] cites a report by Henry Copeland, a European online publishing consultant, that the New York Times' web site "has sold more than 160,000 print subscriptions over the last two years and is the paper's #1 source of subscriptions" even though NYTimes.com now has more daily readers than the newspaper itself.

In other words, the quality of the reporting on NYTimes.com compels online readers to become print subscribers.

MediaSavvy also states that "as monopolists accustomed to 25% profit margins, newspaper publishers are intellectually ill-equipped to publish on the Internet." In this case, although not in so many words, even Neil Budde, founder of the Wall Street Journal Online and therefore the hero of the paid-content movement, agrees.

In an interview, Budde tells PaidContent: "I actually think right now too many people are making a rush towards the subscription model because everybody says now is the time they should go for that. That's probably as bad for some people as starting off with the free model was back then. It really needs to be much more specific to the circumstances of the particular company, product, and competition."

In other words, publishers need something more to sell than just the contents of the daily newspaper - something unique, market-oriented and customer-focused.

Quality sells. But, then again, in the monopolies most newspapers have enjoyed for decades mediocre has sold almost as well. The Internet flattens that information hierarchy by amplifying the choices available to readers, who are showing the willingness to pay for the good stuff (the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times crossword) and read the rest for free.

The Poynter Institute this week is sponsoring a conference on Journalism & Business Values. James Naughton, Poynter's president, defined the conference's goal in his opening remarks: "What we hope to attain in the next day or so is a more reasoned dialogue about why journalism matters to the business and why business matters to the journalism."

Journalists shouldn't have to learn why business matters - in 1975 there were 1,756 daily newspapers in the United States; in 2001 there were 1,468, 16 percent fewer.

Publishers shouldn't have to learn why journalism matters - only 54 percent of U.S. adults read daily newspapers, as do only a third of families headed by someone age 25-34 [see The Lost Generation].

Quality sells. Relevance matters. The real lesson both the newsroom and the boardroom need to learn is that, in the age of the 24-hour scroll, the micro-fragmentation of electronic media, and the constant clamor for a news consumer's attention by everyone from the New York Times to yours truly, all that's left is the journalism.

Links

![]() Columbia Journalism Review Why Information Will No Longer Be Free

Columbia Journalism Review Why Information Will No Longer Be Free

![]() PaidContent Interview with Neil Budde

PaidContent Interview with Neil Budde

![]() Poynter Institute Journalism & Business Values

Poynter Institute Journalism & Business Values

![]() Pressflex NYTimes.com daily users top parent's print circulation

Pressflex NYTimes.com daily users top parent's print circulation

February 10, 2003

The Shuttle: When is Too Much News Not Enough?

I launched First Draft with the Quality Manifesto, an admittedly self-inflationary headline for a piece that, in its essence, lamented newspapers' lack of innovation and proclivity to run in a pack. Newspapers, I wrote, "are killing themselves with adherence to a self-destructive, journalistic form that emphasizes breadth of news coverage over depth."

David Shaw, the Los Angeles Times media writer, addresses the same issue in a column that questions the over-saturation of Columbia coverage to the detriment of other stories, particularly the coming war with Iraq.

"It's not surprising when all-news radio and cable TV fill the airwaves with one story, hour after hour. They're 24-hour news operations, and on most days there's not enough real news to fill that gaping hole. But newspapers have a different mission, and their readers have different needs. Do readers really want 25 separate stories on the Columbia, as USA Today provided on Monday, along with 45 photos, drawings and other graphic elements (and that doesn't include the four Columbia stories and three pictures in the paper's Life section, or the story and four pictures that dominated the first page of its Sports section)?"

The answer, of course, is no, and Shaw finds the news media "once again guilty of confusing the spectacular with the significant."

I would also convict newspapers, once again, of focusing inward - on themselves, on their competition, on the notion that nothing is bigger than the Big Story of the moment - instead of outward, on their readers and on their role in the larger environment of omni-media.

In a column last November, Shaw interviewed Jay Harris, the San Jose Mercury News publisher who quit over newsroom cutbacks ordered by the paper's corporate parent, Knight Ridder. They were talking about the political news, but Harris' comments are apt in the context of the shuttle coverage. Shaw wrote:

"(Harris) thinks journalists talk too much to each other -- and not just in speeches. He thinks many stories they write and broadcast, ostensibly to enlighten the public, are also -- even if only subconsciously -- aimed primarily at their colleagues and their sources, rather than the reading and viewing public."

The quote clip came from MediaMinded, who added this comment to Harris' remarks: "Reporters will jump through hoops to find some subtle little nuance or extra little factoid that the competing paper missed, but which adds next to nothing to the narrative." [Thanks to Rhetorica for the pointer.]

Newspapers' compulsion to scrum a story under mounds of incremental reporting is fueled by the relentless pounding of 24-hour TV news. I have been in more than one newsroom during a major story and watched assignment editors futilely attempt to keep pace with what passes for broadcast reporting.

Of course, destruction of the Columbia was a huge story. Of course, it was a human tragedy. (Although as Orville Schell, dean of the UC-Berkeley journalism school, points out, the excessive coverage of the shuttle disaster "raises questions about the equivalence of human tragedy" such as the "wars, famines and epidemics that last years, maybe a lifetime (that) don't receive anywhere near this much attention.") And, of course reporters are raising legitimate questions about NASA's funding and safety record.

What is important for newspapers to remember, or perhaps relearn, is, as Shaw stated, that "newspapers have a different mission, and their readers have different needs."

I am sure many people will disagree with Shaw's assessment that the news media mistook the "spectacular with the significant" in covering the shuttle - I myself read every Columbia story Sunday morning in the New York Times and the San Francisco Chronicle - but I think what he yearns for is more perspective by newspapers, a longer view on the contextual importance of an event, something that extends beyond the reach of today's CNN scroll bar, in planning and executing their coverage of a Big Story.

You can't disagree with that.

UPDATE: Jonah Goldberg tackled the same question, and raised the same issue of perspective, in the Wall Street Journal. He concluded: " 'The Columbia is Lost' story involved large themes, important policies and billions of dollars mixed in with drama, tragedy and heroism too. If not this, then what kind of story should the media go overboard about?" [Thanks to cut on the bias]

Links

![]() David Shaw How the loss of Columbia eclipsed all other news

David Shaw How the loss of Columbia eclipsed all other news

![]() Jonah Goldberg Spaced Out -- Another maudlin, media-crazed moment. But hold the scorn.

Jonah Goldberg Spaced Out -- Another maudlin, media-crazed moment. But hold the scorn.

Knight Riddance

Knight Ridder is conducting a "$100 Million Scavenger Hunt" to cut costs throughout the 31-newspaper chain, the nation's second-largest, according to a story in the New York Times.

A team of editors, according to a company memo, is making the following money-saving suggestions:

Creating national teams of reporters to provide coverage of wars, politics and major events.

Centralizing the copy-editing function, allowing different newsrooms to share the editors who fine-tune articles and write headlines and photo captions.

Charging for some free listings, like movie timetables, stock tables and obituaries.

Cutting corporate costs related to diversity initiatives.

Considering the inclusion of strips of advertising at the bottom of sections' front pages.

Cutting staff positions.

As the memo circulates, the executive editor of the Miami Herald, a Knight Ridder publication, and one of the paper's columnists publicly debate whether or not the Herald is but a shadow of its former greatness.

Last week columnist Jim DeFede asked: "What happened to The Herald?" And answered: "There are not enough reporters, editors and photographers to cover this community the way it deserves to be covered."

DeFede blamed Knight Ridder for cuts in staff and benefits, saying, "It was sobering, sitting in the newsroom of one of the largest papers in the United States, and listening to some of the employees debate whether they would have to drop their medical coverage because they couldn't afford the new premiums (while) corporate executives were granted $10 million in bonuses."

Today, Herald Executive Editor Tom Fiedler asks his own question: "Was there a time when we were better? Show me when." And makes this assertion: "Knight Ridder's profit goals (earnings) are more modest than some of its newspaper-industry peers, including Gannett (earnings), publisher of USA Today, or the Tribune Company (earnings), which publishes the Sun Sentinel in Fort Lauderdale."

Defensiveness is becoming a Knight Ridder trait. Just last week, CEO Tony Ridder used the Poynter Institute as a platform from which to proclaim that "impact journalism" is alive and well in the chain.

Links

![]() New York Times Cost Cuts at Knight Ridder

New York Times Cost Cuts at Knight Ridder

![]() Jim DeFede What happened to The Herald?

Jim DeFede What happened to The Herald?

![]() Tom Fiedler Herald's formidable past doesn't outshine its present

Tom Fiedler Herald's formidable past doesn't outshine its present

February 07, 2003

Pipe Dream Come True

SF Weekly tells the story behind the New York Times investigation into the deadly factories run by pipe manufacturer McWane Inc., which began with some old-fashioned digging by a UC-Berkeley student who audited an investigative reporting seminar taught by former 60 Minutes producer Lowell Bergman.

The student, Robin Stein, was auditing the class because Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism had rejected her application.

Weekly writer Matt Smith says Stein's success offers hope for a jaded profession.

"Several years later, while attending journalism graduate school, I was flabbergasted at the imperious portent that my fellow students ascribed to the writing of the news: Was it a craft, a profession, a calling? Blah, blah, blah. Whatever happened, I thought, to this fun thing that almost anyone could do -- but that some people actually got paid for?"

Stein's enthusiasm is evident in her conversation with Smith: "I've never done anything before where I woke up in the morning and was excited to go there. I was talking to people about things that are so important in their eyes." Go read.

Links

![]() New York Times Dangerous Business

New York Times Dangerous Business

![]() Frontline Companion program to Dangerous Business

Frontline Companion program to Dangerous Business

News Flash!

![]() The San Francisco Chronicle put together a very readable, and apparently exclusive, story today on how electronic disturbances leaping through the upper atmosphere might have caused the destruction of the space shuttle Columbia.

The San Francisco Chronicle put together a very readable, and apparently exclusive, story today on how electronic disturbances leaping through the upper atmosphere might have caused the destruction of the space shuttle Columbia.

The story, played under the effectively tabloidish headline "Cosmic bolt probed in shuttle disaster," demonstrates how knowledge - in this case Sabin Russell's background in science and technology reporting - initiative, strong, clear writing and a good graphic illustration can combine to produce a compelling story about an unexplained event.

Here's what happened: An amateur San Francisco astronomer, who for now has chosen to keep his name out of the press, used a digital camera to make a photograph of the eastward-bound Columbia streaking over California. To the photographer's amazement, the image showed a "purplish, luminous corkscrew" apparently striking the spacecraft.

When NASA sent a former astronaut to the photographer's house to review the image, "a Chronicle reporter was present when the astronaut arrived. First seeing the image on a large computer screen, she had one word: 'Wow.'"

That's good stuff.

It is easier to write about scientific phenomena when they have other-worldly names such as "sprites, blue jets and elves," as these do, but Russell patiently and cleverly weaves fact and anecdote to explain the mysteries of high reaches of the sky.

For example:

"Physicists have long jokingly referred to the lower reaches of the ionosphere -- which fluctuates in height around 40 miles -- as the 'ignorosphere,' due to the lack of understanding of this mysterious realm of rarefied air and charged electric particles."

And:

"Originally, it was thought that the electrical charges in the thin atmosphere 50 miles above Earth were too dispersed to create infrasound. But Los Alamos National Laboratories physicist Mark Stanley said that, on closer inspection, 'we've seen very strong ionization in sprites' indicating that there were enough air molecules ionized to cause heating and an accompanying pulse -- a celestial thunderclap, as it were."

Of course, maybe the amateur astronomer didn't photograph a sprite or a blue jet. Maybe his camera trembled just enough during the time exposure to cause a streak, but, as Russell writes, "should the photo turn out to be an authentic image of an electrical event on Columbia, it would not only change the focus of the crash investigation, but it could open a door on a new realm of science."

Links

![]() San Francisco Chronicle Cosmic bolt probed in shuttle disaster

San Francisco Chronicle Cosmic bolt probed in shuttle disaster

![]() Scientific American Blue Jets May Link Thunderstorms to the Ionosphere

Scientific American Blue Jets May Link Thunderstorms to the Ionosphere

February 06, 2003

Bigger is Better (Duh!)

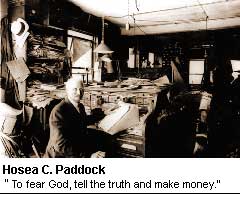

You just have to love Hosea C. Paddock. When H.C., as his descendants call him, went into the newspaper business 120 years ago, he forthrightly proclaimed his intentions with this slogan: "Our aim: To fear God, tell the truth and make money."

You just have to love Hosea C. Paddock. When H.C., as his descendants call him, went into the newspaper business 120 years ago, he forthrightly proclaimed his intentions with this slogan: "Our aim: To fear God, tell the truth and make money."

Now, I can take or leave the God part (but giving our president's affinity for the Big Guy - "The liberty we prize is not America's gift to the world; it is God's gift to humanity." - maybe I should rethink that position), however, the rest of H.C's motto represents my kind of thinking.

The little paper H.C. Paddock started in a Chicago suburb grew into the Daily Herald, the third-largest paper in Illinois and one of the nation's most abundantly staffed.

Mark Fitzgerald of Editor & Publisher reports that the 149,000-circulation Herald "maintains a newsroom that is nearly twice the industry average -- and disputed rule of thumb -- of one full-time equivalent (FTE) for each thousand in circulation."

Why? Douglas Ray, CEO of Paddock Publications says so-called "overstaffing" is an "essential part of how we do business here."

"If you have a long-term stake in a market," Ray says, "you have to cover the communities intensely. You can't do that with smoke and mirrors -- it takes people to do that."

And is this way of thinking good for business? Ray says the company "could be much more profitable than we are today" but that would undercut its larger goal. "The paper has had 21 years of circulation growth without missing an ABC [Audit Bureau of Circulations] reporting period. It takes a number of people to do that."

The 1-to-1,000, newsroom-to-circulation metric has a specious history, and, according to Lori Robertson, managing editor of the American Journalism Review, who looked into the origins of this rule of thumb and found them elusive, is widely criticized by newspapers executives and newsroom managers alike.

"It's been called an industry standard, the norm, an average and a rule of thumb. It's also been called a myth, folklore and flat-out wrong. Yet it's often cited--even if it's being derided--and widely known by most in the newspaper business."

It's wrong, indeed, Rick Edmonds, a researcher for the Poynter Institute, told Robertson. He said the industry norm is now about "1.2 to 1.4 or so FTEs per every 1,000 in circulation."

(Edmonds was also involved in a project by Poynter and the Project for Excellence in Journalism that found the 218,000-circulation Fort Worth Star-Telegram to be the "best-staffed paper in America" - 370 FTEs.)

The unanswered questions in both Edmonds' study and Robertson's story, though, are these: What are all those FTEs doing? Are they reporting? Are they writing and editing stories? Or are they processing pages and performing other pre-press functions that once belonged in the mysterious realms of the backshop but were brought by technological changes into the newsroom?

(Please, copy editors, call off the posse! I mean no disrespect to the wordsmiths and paginators on the desk, but, let's face it, without the reporters and their stories there is nothing to wordsmith or paginate.)

Few media magazines have a more conservative editorial philosophy than Editor & Publisher. It is, after all, a trade publication whose revenue depends on the very institutions it is covering, so criticism and coverage of sensitive issues is handled gently. It is a good sign, then, that the cover story in this week's issue is "The Missing Link Between Quality and Profits." Maybe the industry is starting to wake up.

Links

![]() Editor & Publisher Some Publishers Believe in Big Newsrooms

Editor & Publisher Some Publishers Believe in Big Newsrooms

![]() Editor & Publisher The Missing Link Between Quality and Profits

Editor & Publisher The Missing Link Between Quality and Profits

![]() American Journalism Review Rule of What?

American Journalism Review Rule of What?

![]() Poynter Institute The Best-Staffed Newspaper in America

Poynter Institute The Best-Staffed Newspaper in America

February 05, 2003

Tony Ridder Defends his DNA

Tony Ridder, chairman and CEO of Knight Ridder, apparently couldn't take the being the poster boy for all that is wrong with corporate journalism any longer.

Ever since his company announced it was doling out millions to company managers after slashing newsroom budgets, he had been subjected to derision from journalistic watchdogs, among them former Washington Post ombudsman Geneva Overholser, who lectured him in her Poynter online column: "If the mantra used to be: 'We've got to be a strong business in order to do strong journalism,' it now seems quite openly to have become: 'We've got to make higher profits than all the others.'"

Overholser turned her next column over to Ridder, who defended his reduction in the number of Knight Ridder employees by 7.3 percent last year in order to produce 31 percent increase in revenue for the Q4 of 2002 (and a 28 percent rise in the KRI stock price from a $51.54 in July to a close of $66.04 yesterday).

"Knight Ridder is a public company. While its successes can be measured in many ways - and we regard first-rate journalism as a critical one - its return to shareholders is another. As our shareholders should, they remind us of this reality frequently ... Other publicly-traded newspaper companies all work under exactly the same pressures."

Ridder maintained that "impact journalism" remains the norm at Knight Ridder newspapers and asserts that "public service projects and investigations in our newspapers is impressive."

Overholser, in her earlier column, was skeptical and pointed to a book entitled "The Big Chill" that found a direct, deleterious relationship between the quest for higher profit margins and investigative journalism. After examining 15 years of reporting at the Chicago Tribune, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the Philadelphia Inquirer (a Knight Ridder newspaper) authors Marilyn Greenwald and Joseph Bernt concluded:

"There was less interest in 1995 in targeting private institutions, executives and employees than there had been in 1980. These findings suggest that a change has occurred at these prestigious metropolitan papers -- a change that is affecting content, reducing the investigative reporting so prized by journalism professionals and the watchdog mission journalism educators have long ascribed to the press."

Overholser has been all over the issue of profits vs. quality journalism, citing a report from the Aspen Institute's Conference on Journalism and Society that recommended newspaper companies establish a "journalistic values" committee on media companies' boards of directors.

"It is the rare communication company that specifically regards journalistic excellence as an oversight responsibility of its board. Few feel obliged to name experienced journalists as directors or establish 'journalistic standards' committees comparable to finance, audit and compensation committees. While there are certain reservations to this approach, formally fusing 'journalistic DNA' into the corporate governance fabric is a high-impact initiative worthy of serious exploration."Read the full report (PDF)

Journalistic DNA. I like that. Maybe Tony Ridder needs a few more strands of it.

Links

![]() Geneva Overholser What Counts Most in a Newspaper Company

Geneva Overholser What Counts Most in a Newspaper Company

![]() Geneva Overholser What Does YOUR Media Company's Board Look Like?

Geneva Overholser What Does YOUR Media Company's Board Look Like?

![]() Tony Ridder Tony Ridder Responds

Tony Ridder Tony Ridder Responds

![]() Aspen Institute Journalism and Commercial Success: Expanding the Business Case for Quality News and Information

Aspen Institute Journalism and Commercial Success: Expanding the Business Case for Quality News and Information

February 04, 2003

Good Ol Days? Hildy Who?

Mike Clark, omsbudman for the Florida Times-Union raises this question: "The 'good old days' of news: Did they really exist at all?"

Part of his answer is provided by Howard Kurtz, the Washington Post media reporter:

''There was no golden age (of journalism). There was certainly a time when politics and government were treated more substantively and seriously by the media. But what some people mythologize as the good old days was a time when women wrote mainly for what was known as the women's pages, when newsrooms were almost entirely white, when news about Negroes was treated differently than news about whites. Reporters of the Front Page mold may have been more in tune with the people they were writing for, but they were less educated, less specialized, less knowledgeable and sometimes drunker than today's journalists."

These things are true. The days of Hildebrand Johnson may not have been golden, but they were lively and that energy is often the lacking ingredient in modern newspapers, which, because they are reported and edited by more educated, more specialized and more knowledgeable (and certainly less drunk) journalists, have had much of the spirit bred out of them.

That said, today's newspapermen and women have the opportunity to make these times the beginning of a golden age of journalism. Never before has such a convergence of talent and technology taken place. Properly focused - on the political, cultural and environmental dynamics that are changing our communities and our country (instead of on the mundanities of process and petty police news) - these forces can reinvigorate newspapers as a source of needed information and sought-after opinion that can be delivered to consumers across multiple platforms.

Recently, while speaking to a class of journalism students in San Francisco, several of them lamented the paucity of newsroom jobs awaiting them after graduation and expressed fears for the future of their would-be profession.

Nonsense. An array of opportunities awaits this new generation of journalists, choices that those of us who went before them didn't have and couldn't even imagine. The appetite for news in this country has never been more voracious. How newspapers choose to feed this beast will determine if these days, indeed, can be a golden age.

(Thanks to OmbudsGod for the tip).

February 03, 2003

Covering the Coverage

Staci Kramer, an editor and columnist with the Online Journalism Review, generally praises how newspapers' online news operations handled coverage of the space shuttle Columbia.

She points out how the newspapers in the racks on Saturday "seemed hopelessly outdated" by the technology-driven information revolution that had occurred since the Challenger disaster in 1986.

Kramer at once lauds the Internet as source of information and communication and chastens its adherents for spreading rumor and misinformation under the guise of fact.

She also dismisses as "poppycock" the notion put forth in the Blogosphere, and reported by the New York Times, that "conventional media does not have the variety of technical talent" needed to provide multimedia coverage to such an event.

Kramer adds: "In fact, much of the information being shared on blogs and in communal discussions as awareness about Columbia spread came from 'conventional' media outlets. It's not that I think everything the mainstream media does is right; it's just that I don't see journalism through the us versus them filter so many seemed determined to employ."

Agreed. And that's not poppycock.

Links

![]() Staci Kramer Shuttle Disaster Coverage Mixed, but Strong Overall

Staci Kramer Shuttle Disaster Coverage Mixed, but Strong Overall

![]() New York Times A Wealth of Information Online

New York Times A Wealth of Information Online

The Lost Generation

It's not news that U.S. newspapers penetrate an increasingly smaller percentage of the population each year, but perhaps it is surprising how worthless the printed product is to the generation of 18-to-34-year-olds.

In an anecdote-rich piece today, Newsday declares that the growing distaste of younger people for newspapers "is seen by many as a crisis that threatens the long-term survival of some celebrated news organizations."

The story reports on inertia-breaking efforts by big media companies to create products that will entice this lost generation - the Chicago Tribune's RedEye tabloid, "alternative" throwaway papers from Gannett and Knight Ridder, a Topeka Capital-Journal music web site.

Demographics expert Peter Francese, who lectured publishers last month on the need for service, context and dialogue, said these experimental departures from the one-size-fits-all news product" are laudable because "there isn't one community to serve. It's gone. ... It's now a matter of serving niches rather than trying to be all things to all people."

But John Morton, perhaps the most frequently quoted newspaper industry analyst, is skeptical. He told Newsday: "You've got to bear in mind everything the newspaper industry has tried in the past. There have been programs of putting newspapers in the classroom and special pages and sections aimed at the young. They've pumped up entertainment and sports and celebrity folderol, and none of it has worked."

Here are some numbers:

![]() Only 33 percent of U.S. families led by someone age 25 to 34 bought a daily newspaper in 2001 compared with 63 percent in 1985.

Only 33 percent of U.S. families led by someone age 25 to 34 bought a daily newspaper in 2001 compared with 63 percent in 1985.

![]() Nationally, 41 percent of young adults read a daily newspaper last year.

Nationally, 41 percent of young adults read a daily newspaper last year.

![]() Between 1986 and 2002, the share of newsweekly (Time, etc.) readers under the age of 35 shrank from 44 percent to 28 percent.

Between 1986 and 2002, the share of newsweekly (Time, etc.) readers under the age of 35 shrank from 44 percent to 28 percent.

The generation prefers magazines, the Internet, radio and TV to newspapers. One anecdote in the Newsweek story highlights the technology gap between young people and newspapers but also emphasizes the cultural divide between the Watergate-era Boomers running newsrooms and the Monica-gate Nexters who view one talking head that same as the next.

"Meghan Attreed, in her first year at Hofstra University in Hempstead, admits to wanting the news with a large dose of entertainment. The 18-year- old from Connecticut is a fan of 'The Daily Show' on the Comedy Central cable channel. 'It's entertaining but you still get the basic news,' she said referring to the spoof of newscasts from ABC, CBS and NBC. 'You will know there's an attack on Iraq but [the anchor] makes light of it.'"Attreed, who works at the campus radio station, also routinely checks out newspaper Web sites, though she rarely reads the dailies themselves. 'Young people, like me, are used to things going fast because we were brought up in the technology age. Why sift through the entire newspaper when I can just go online and get it [a news story] in 30 seconds,' she said."

Links

![]() Newsday Why Won't Johnny Read?

Newsday Why Won't Johnny Read?

February 02, 2003

Shuttle disaster front pages

Be sure to visit the Newseum's collection of newspaper front pages to see how shuttle coverage was played in the U.S. and around the world. It changes daily (of course), so do it today.

February 01, 2003

Covering Columbia

Here's a roundup of how major newspapers have reacted to the crash of the space shuttle Columbia, including the headlines for their packages. The Florida and Texas papers were naturally the most ambitious.

Here's a roundup of how major newspapers have reacted to the crash of the space shuttle Columbia, including the headlines for their packages. The Florida and Texas papers were naturally the most ambitious.

Florida Today, which describes itself as "serving Florida's Space Coast," put out two extra editions and an online package, Columbia Lost. UPDATE: Poynter Online did an email Q&A with the editor of Florida Today on his paper's coverage. Here's an excerpt:

"The space program touches all parts of our community and this was an intensely local story for everyone. ... There was never a question about doing the Extras, we knew they were needed and we would act."

The New York Times created a special online section: Loss of the Shuttle.

The Houston Chronicle (Tragedy Over Texas) folded its coverage into its existing SpaceChronicle section and put out an extra print edition. See front page image here.

The Dallas Morning News (which also called its package Tragedy Over Texas) simply compiled a list of stories but also offered an online editorial.

The Miami Herald (The Shuttle Columbia Tragedy) also put out an extra print edition and published the entire eight pages online as a PDF.

The Orlando Sentinel published an extra. Here are the stories. Here is the front page.

The Florida Times-Union (America Loses Columbia) has video-rich special section.

The Los Angeles Times only compiled a list of stories.

The Washington Post (Columbia Shuttle Tragedy) put together a special page.

The Tampa Tribune (Space Shuttle Lost) published and extra edition and has an online package.

The San Antonio Express-News ('Columbia is Lost') has a thin online package, but it did publish an extra.